The Digitalisation Project Castle Huis Bergh is the intellectual property of the Stichting Musick’s Monument. Ing Hans Meijer was responsible for the technical realisation; Dr Willem Kuiper for the scholarly input. Thanks are also due to the Anjer Cultuurfonds Gelderland; the Stichting de Verenigde Stichtingen “De Armenkorf” in Terborg and “Het Gasthuis te Silvolde”; Mrs P. Tijdink-Hermsen; Mrs L.J.C. Meijer-Kroonder; and the Giese family.

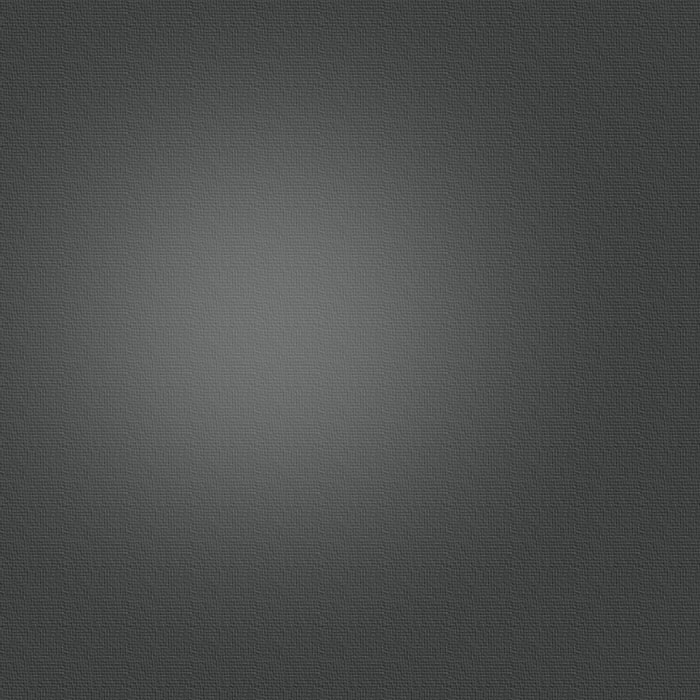

Polack, Jan (ca. 1435-1519, Munich) Germany, Munich The recognition of the True Cross

(legend of St Helen) 1486.

In 324 AD Helen, mother of the first Christian emperor Constantine the Great, is supposed to have found both the cross of Jesus and the crosses of the two condemned thieves. Helen stands depicted with a golden crowning glory and a garment of brocade, whose train is carried by a page. Before her lie the three crosses. In the foreground, a dead person awakes, having come into contact with the cross of Christ. Formerly property of the Labach monastery in Lower-Austria.

Constantine the Great was the first emperor to grant freedom of

religion to the Christians within his vast empire. The events that led to this decision are legendary. When emperor Constantius died, his son Constantine was acknowledged as his successor. Unfortunately, there was a second pretender, a man named Maxentius. Tradition has it that the day before Constantine was to do battle with his enemy, he had a vision of a cross, and the words ’in hoc signo vinces’ (’you will conquer in this sign’) written next to it in the sky. The emperor-to-be then made the Christian Church his ally against Maxentius and did indeed vanquish his enemy. The fact that he tolerated the practise of the Christian faith in his empire did not mean that Constantine himself was an avowed Christian. Once this religion had proved its power in combat, however, the emperor’s interest was aroused. He is said to have sent his mother Helen to the Holy Land to search of proof of the existence of Jesus Christ on earth. Her discovery of the true cross is the subject of this panel. The lady in the middle with the gold leaf halo surrounding her head is Helen, appropriately dressed in majestic clothes and attended by two maidservants and a page. These four catch the beholder’s attention with their lustrous skin colour. In those days a white complexion was a sign of nobility, an distinguishing feature of the leisured classes, in sharp contrasting with the weather-beaten skin of working-class people. In this case, it is also intended to contrast with the dark complexion of the Oriental locals. We see a man on the left holding a shovel, who has dug up three crosses: two small ones lying on the ground next to Helen, and a larger one in the foreground. Since Christ was not the only person ever crucified, not every cross buried in Palestine’s soil was the true cross. Helen and her team, realizing this, tested the three crosses they found: they laid a sick man on each of them, believing firmly that the one true cross would cure him. As the painting shows, it did, and many other sick people were brought to this medicinal piece of wood. A man on crutches leaves the surprisingly northern European-looking nearby town of Jerusalem, hurrying to his cure, together with two old men and a woman on a stretcher. In the upper left hand corner of the panel, we see people hanging out of their windows and standing in their doorways, discussing the miracle they have just witnessed.