Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken jr.

1761 - 1768

Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken was born into the family of Johan Lodewijk Dulcken and Catharina Koning in the summer of 1761 and baptised on 9 August 1761 in the Gereformeerde Kerk in Amsterdam/ Sloterdijk. His call sign is Louis. He has a brother, Daniel Lodewijk, who is one year old and a big sister, Susan Maria, who is four. His father is a master organ and harpsichord builder and they live next to the Carthusian cemetery in Amsterdam.

As a small baby, less than six months old, he moves to Hasselt in early 1762. There, his father rented a large house in Nieuwstraat.

Nothing of his life in Hasselt can be found in the archives, but a picture can be drawn of his living environment and the events that took place there in his young life. He may later remember the following from his childhood in Hasselt:

When he is almost two, a little brother is born. His parents name him Johan Daniël, after his famous grandfather. Unfortunately, this little brother does not live to be one year old. On 20 April 1764, he is buried in the cemetery behind the Reformed Church. Still in the same year, another little brother is born on 22 July, again named Johan Daniël.

1765

Johannes Lodewijk is now old enough to explore the world outside the house.

His parents' house is on Nieuwstraat; this street runs from Markt, where the town hall is, to the canal. Across the canal is a bridge with a lock in the canal that also serves as a flood barrier. Across the canal, on Gasthuissteeg, stands an old monastery building; the alley ends in a rampart with city walls.

C. Springer, het oude Gasthuis aan de Gasthuissteeg.(1862)

Along Nieuwstraat, paved with cobblestones, are houses and the workshop of a blacksmith. To the right of his house is Regenboogsteeg, formerly also called Ragebolsteeg. In Regenboogsteeg is a tobacco plantation that belonged to the Van Benthem family, and also a roof tile factory. Both are no longer used, but you can still see where they stood. Behind their house is a large garden, where his father grows vegetables. Between the garden and Rainbow Street is a wall, with a passage to the street at the end.

In the spring of 1766, Johannes Ferdinandus is born and baptised on 16 March. The little boy dies before he is six months old. Once again there is grief in the family.

Meanwhile, Johannes Lodewijk turns six, the age when he can go to school. This means he is taught reading, spelling, numeracy and writing. To learn these basic skills, his parents have to pay 18 guilders a year. He can attend school every morning and afternoon and is free on Wednesday afternoons.

In January 1768, another little brother is born, baptised on 13 January. His parents name him Ferdinandus. The little boy lives only a month and again there is grief. Unfortunately, it is common for children to die at a young age. A large proportion of children do not make it to the age of 20. Children die of childhood diseases, poor drinking water and because parents are in poverty.

Walking through the streets of Hasselt, Louis sees poverty everywhere. The houses are poorly maintained; sometimes they are hovels. In some places where houses have been demolished, empty spaces appear in the streets. There are also many farms in the city, often with a dung heap on the side of the street. The gutter, which provides drainage for rainwater, is sometimes open, but often there is a plank over it, making the street less dirty.

He sees collection boxes hanging in various places. Wealthier residents can put their contributions there, which can be used to help poor people by the diaconate. In December 1768, Johannes was born. His call sign is Jan. He is baptised in the big church on Boxing Day. They are now five children at home; his eldest sister Susan Maria is just 11.

When they go to church, he and his little brother and sister sit with mother. Father sits in another part of the church with the men. Close to the main door is a pulpit. Usually Pastor Noortbergh preaches.

Interieur Hervormde Kerk Hasselt.

There is no organ in the church; it was destroyed by lightning and fire 50 years ago. The church and the city council have no money to have a new organ made. His father could well do it; he has built organs before. Now the place is empty and when there is singing, there is a cantor who indicates the melody. Hermen Huninck is an organist, but probably has little to do since the fire of 1725.

His father is often away from home; then he leaves on a barge to Amsterdam, sometimes even to Middelburg.

He then takes one or two harpsichords with him. They lug these from their house through Nieuwstraat, across Markt and then via Veersteeg to Veerpoort. Outside the Veerpoort lies the Zwartewater. From there, the barges go to various places along the Zuiderzee. Each turn boatman has his own destination. His father often goes with him; so he knows all the skippers.

When father is away, the servant just keeps working on the harpsichords that are in the workshop. The servant also lives in their home and has his bedroom at the very top of the house.

Sometimes a man comes to the door with a note, Mr Van der Werff. He is robed and brings a message from the mayor or the council. His father then has to appear at the town hall again. Sometimes father is not at home and then mother or his eldest sister takes the paper. When this man comes to the door, Louis already knows exactly what he has come to do. Sometimes there is more to it, as when the rod-bearer and some helpers bring two harpsichords.

1769

When Johannes Lodewijk was eight years old (1769), his father bought the house where they had been living for six years, and on Hofstraat he bought a workshop

This is necessary because the house on Nieuwstraat is becoming too small. Because Grandma Dulcken has come to live with them, there is a lack of space. When grandma, who lived in Brussels, comes to live with them, she is ± 65. Grandpa, whom he never knew, died long ago.

His father brings all kinds of materials to Hofstraat and sets up his workshop there (Plot A262) When Louis walks to the workshop, he sees small businesses and shabby houses in Hofstraat. At the end of the street is a number of cottages next to each other, which people call the ‘Armenstraat’. Often, because of the smell, there are arguments over the gutter that runs down Hofstraat.

Werkplaats Dulcken links

Next to the residence on Nieuwstraat is a large building, owned by the court martial. Louis often sees people going in and out there. In the evening, the night guards come there, going through the town two by two, and sometimes he hears them shouting. Occasionally there is also a whole group at once; then the men march through the town in a column. The night guards carry weapons. At night, music can often be heard coming from the house of the court martial. Then there is a meeting or party when the guilds meet there. People then call the house Guild House.

His father has a quarrel with the lords of the court martial. The big garden they had got a lot smaller. His father then bought a piece of land behind the Wall, where he created a garden. De groente wordt in de herfst in de kelder opgeborgen. Every year father buys a cow or a pig in the autumn, which he has slaughtered by the Jewish butcher Salomon Abrahams or Albert Berend van der Werff . At home, the meat is smoked so they have food all winter.

1772

By now Louis has turned 11 and is big enough to walk around the city by himself. Walking out of Nieuwstraat, he comes to the canal where mostly rich people live.

C. Springer, Scenery on the Hasselt canal.

Oil lanterns are everywhere in town, especially in the wealthier neighbourhoods such as Hoogstraat and Ridderstraat; some 30 of them. A little further on he comes to the Venepoort, which gives access to the dyke to Zwartsluis and the post road to Staphorst. Turning left, he goes along the city wall to the Raampoort, passing through the poor neighbourhood. Further on, he comes to the Veerpoort, which separates the town from the quay with ships. Along the Vispoort, he walks to the Enkpoort, which gives access to the dike to Zwolle. This is an old stone dike; in a bit of a storm, the water sloshes against it. Another short stretch along the canal and then he is home again; a walk of about 1,200 metres.

It is clear that his hometown is a small fortified town, protected on one side by the Black Water and on the other by the moors. Yet every year in June and September, Hasselt is buzzing with activity. That is when the hannekemaaiers from Hesse arrive, taking the ferry in Hasselt to Hoorn and Enkhuizen. Seasonal workers will start cutting grass in North Holland. In one month, 10,000 workers are brought over. They are given shelter for one or more nights in inns or in people's homes. They return in September. Two months in the year when people crowd the streets, full inns and often quarrels and noise. Louis hears German being spoken all over the streets then.

He often walked from his home across Market Square to the workshop on Hofstraat. But in January 1772, it is special. When he gets to the town hall on the Markt, he knows that his father is imprisoned up there somewhere. Fortunately, he is soon released, but it makes a deep impression on the boy.

Something else that makes a deep impression is that there is not enough bread for sale in Hasselt that year. There is famine, the bakers have run out of grain and flour is nowhere to be had. He hears that the magistrate has asked the city of Zwolle for help. Fortunately, the city there is in a position to buy grain.

Training

When Louis finished primary school, he could attend French school. For several years, Lambert ter Bruggen has established a school in the old monastery building in the Gasthuissteeg. Besides the regular school subjects, he also learns French, and at home he learns from his father how to build a harpsichord.

His father, meanwhile, has started something new. On his travels through Holland, he has heard about a new way of building harpsichords. In the workshop, he goes to try out the new mechanism for this instrument. His father shows him that if you strike a string with a kind of hammer, you can produce a completely different sound and tone. Johannes Lodewijk finds this fascinating. His father believes this is the future. There will come a time when all harpsichords will be built this way. Now it is a matter of trying out which way the action works best.

Louis can probably often be found in the workshop. He learns at an early age how to handle tools and likes to work very precisely. With his father he gets an excellent education to later build beautiful harpsichords himself. He wants to follow in the footsteps of his father and his famous grandfather. Thus, important building principles are passed on from father to son.

His father is now always absent for long periods. On his return, he talks about his work in Antwerp, building new harpsichords and selling them in Leuven and Ghent. He can also rebuild harpsichords and put in new mechanisms. It is in high demand, so there is plenty of work. Perhaps Louis went with him to Antwerp several times. Did he continue his skills in building harpsichords at home in father's absence on Hofstraat? Did he try out ways to improve the instrument's mechanics? Did he experiment with different types of mallets? It is clear from the remainder of his life that he became skilled in making harpsichords at a very young age. The basis for his later work was laid here in Hasselt.

At the end of his Hasselter period, he still experiences the storm of November 1775. The heavy storm whipped up the waters of the North Sea and the Zuiderzee. The dykes around the Mastenbroekerpolder break and the whole area floods. When Johannes Lodewijk looks out on the city wall to the south-west, it is a large expanse of water with a farmhouse here and there on a mound surrounded by water. The water in the moat also rises to dangerous heights, but Hasselt's city centre narrowly avoids flooding.

Farewell to Hasselt

The year 1776

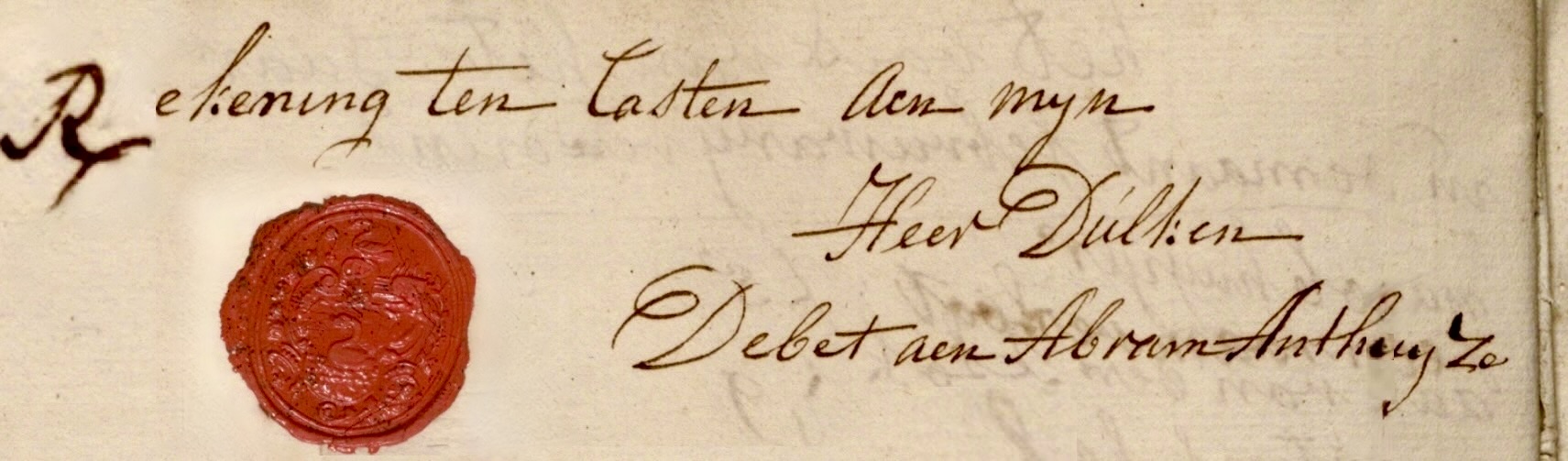

On 7 May 1776, an important meeting of Aldermen and Councils takes place at the Hasselt Town Hall. For Dulcken, it feels like the conclusion of a long period of disagreements and trials. Present at this meeting are: two members of the magistrate, Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken, Abraham Amthuijzen, and Hendrik Fraay de Wilde. Probably Grevensteijn and Waterham are also present as lawyers.

First on the agenda is Dulcken's suit against De Wilde in the case of malicious libel. This trial has been running since 22 September 1771 and now finds an end. Dulcken is vindicated and De Wilde is convicted of spreading malicious libel. Whether Dulcken received the 1,000 guilders compensation is not clear.

Lawyer Waterham demands 188 guilders and 50 pennies from De Wilde as costs and compensation for the defence in this case. He has movable and immovable property of Hendrik Fraay de Wilde seized. He also demands 120 guilders from Frans de Wilde, Hendrik Fraay's brother, who lives in Amsterdam, for having appointed him as representative in this case. R. Sandberg, the other lawyer now also demands 314 guilders from Frans de Wilde. Lawyer Klopman demands 118 guilders from Hendrik Fraay de Wilde and attachment of his goods in connection with costs he has incurred. In total, therefore, this case costs more than 740 guilders. Hendrik Fraay de Wilde tries for months to prevent the sale of his property, but eventually loses.

Amthuizen's lawsuit against Dulcken also ended. In late 1773, Amthuijzen made another attempt to recover the money. A disagreement arises because secretary Exalto D'Ameras has been negligent in settling the case administratively. Dulcken and the secretary do not get along. Grevensteijn says of this: ‘the pawnbroker (Dulcken) is not in good harmony with the secretary’. And that is putting it mildly. Probably Amthuijzen has not been able to prove that his claims are justified and is not receiving his money. The magistrate cannot help him in this. Amthuijzen then appeals to the Knights and Cities. The States of Overijssel submit his request to the magistrate of Steenwijk. Grevensteijn writes a fierce letter in response in March 1776. The magistrate of Hasselt and Amthuijzen are playing under a hat. Normally, the magistrate would never advise appealing to the States. Grevensteijn says the magistrate is acting out of pure rancour towards Dulcken. He blames the magistrate: ‘That his principal seedert has had to continue his livelihood in another place for some time, to this end the Magistrate of Hasselt has contributed not little’. At the meeting of 7 May 1776, the ‘final settlement’ takes place. Dulcken is vindicated in both lawsuits.

After this May meeting, there are few trials in which Dulcken plays a role. Only the court martial makes an attempt before a lawyer to extract money from Dulcken as compensation for high costs. A period is closed. Dulcken moves to Antwerp with his wife and children.

How their lives went on is beyond the scope of this story

On 3 November, Dulcken and his wife are in Amsterdam where they pick up a copy of their marriage certificate at the church in Sloterdijk. In order to start a new life elsewhere, they probably needed this certificate to prove they were married. These records show that the Dulcken family left Hasselt no later than November 1776.

They go to live in Antwerp from where he sells his new invention, the pianoforte, in various cities. On 13 March 1777, he is in Ghent, where he sells a harpsichord with double keyboards and five stops, made in Antwerp in 1740 by Daniël Dulcken, at the Haeze-Wind lodge. Johannes Lodewijk converted his father's harpsichord into a pianoforte and enlarged it to five octaves. To give buyers security, he gave a 10-year guarantee on the mechanism he invented.

DAt’er in den Haeze-Wind op de Koorn-Markt binnen deze Stad te zien en te koopen is een Steirt-Clavecimbel met dobbele Clavieren en vyf Registers, gemaekt door Daniël Dulcke tot Antwerpen in 1740, en nu onlangs door zynen zoon tot vyf Octaven compleet gebragt met een nieuwe ondervindinge, waer door men den Toon kan doen verminderen en ophouden, voor welk mechanicq Werk den voornoemden Zoon de thien eerstkomende jaeren verantwoord.

Yet he did not stay in Antwerp. Around 1780 he settled in Paris, in 1783 in Rue Vieille du Temple and from 1788 in Rue Mauconseil. His last sign of life came from Munich where he went to live with his son. He dies between 1793 and 1795 in Munich because Jan Dulken's remarriage act states: parents dead

Widow Dulcken

VIDEO

There are other signs of Dulcken's plans to leave Hasselt. In January 1776, he rented a cottage in Hasselt for his mother, widow Dulcken. She is thus leaving Nieuwstraat to live on her own. As long as Johannes Lodewijk lived in Hasselt, he will have supported her. That changes when the family leaves Hasselt. The church council minutes of 28 June state: ‘it was recommended to the Brethren Deacons to request cautie stellinge with the H. of the Magistrate for the widow Dulkes’. Apparently, she has turned to the deacons for support and the deacons would like the magistrate to provide surety. This request recurs every meeting.

On 31 October, ‘Susanna Maria Knopfelein, wid. Van Dulcken’ sends a request to the states of Overijssel. From the states' reply sent to the magistrate on 4 March 1777, it is known that the widow has complained that the magistrate wants to evict her from the city by force. She sends along the magistrate's decision, and asks the states to instruct the magistrate to give her permission to continue living in Hasselt.

The magistrate sends a long letter back to the states defending her policy. The magistrate brings up that although the widow says she has been living in Hasselt since August 1769, this was not known to him. It became clear when she had rented a cottage and applied to the deacons for support. It is unknown to him why she had come to live in Hasselt and that she had really moved in with her son. She was visiting there for pleasure it was thought. It was only in January when she was living independently that a deposit could be claimed from her. That surety bond is needed when you want to come and live in Hasselt as a poor person.

Widow Dulcken wrote in her letter that she was not a financial burden to anyone. At most, the deaconry supported her for a number of -six to seven- weeks with six pennies a week. The magistrate called that a lie. Indeed, as soon as she started living independently, she was harassed one after another and still supported by charitable lads. The diaconate also supported her for some time, but eventually stopped doing so. Her name is nowhere to be found in the diaconate's cash books. She does not appear on the long list of the poor permanently supported, nor were any payments made to her during 1776.

In her letter, the widow has also suggested that the magistrate's demand for a surety ‘would have arisen from hatred and discord against her son’. The magistrate calls this slander and falsehood. Finally, a warning to the states: ‘that it is not Your Honourable Majesty's but ours power to permit anyone within the City to live or not, and would have already carried out our orders if we had not wished to inform them beforehand, as we hereby take notice’. The magistrate hopes the states will reject widow Dulcken's request ‘so that we can freely exercise our power and authority within our city’. Yet widow Dulcken is not immediately expelled from the city.

On 2 July 1777, the church council minutes report that after being rejected by the magistrate, the deacons must now request cautie, bail, from verwalter hoogschout. The last time she is mentioned in the minutes is 18 December 1777. Whether she was actually forcibly expelled from the city thereafter is not clear. A few months later, on 18 April 1778, she handed in her attestation, obtained from the church council of Hasselt, to the church council of the Reformed Church in Epe. There she lived for six years before moving to Heerde, where she became a member on 8 April 1784. She was then about 80 years old. She died on 12 June 1789 and was buried four days later in Heerde. One might wonder why she did not go with her son and his family to Antwerp. It was probably not an attractive prospect for her. She left Antwerp for Brussels in 1764 for unknown reasons. According to her, it was to set up a new business with her son-in-law. But is that the only reason? In addition, of course, she heard from Johannes Lodewijk about his conflict with Rev Diepelius. How would the church council react when she wanted to become a member of the Cross Church Olijfberg? And finally, it is not clear whether her son saw Antwerp as a way station to eventually settle in Paris.

Sale of the property

When Dulcken leaves Hasselt, the premises in which he lived and worked become vacant. A month after the ‘final meeting’ in the Raadhuis, the premises in Hofstraat are sold by execution. Since there is no record of Dulcken being bankrupt or of any distraint/pledge on the property, it is more likely that the workshop was simply sold by auction. The property is bought by Jan Admiraal, painter and glazier. Actually, it is only half of a property, the other half having long been owned by Klaas Admiraal who also established his business there. Jan Admiraal pays a purchase price of 15 guilders and 19 pennies.

The house on Nieuwstraat remains empty for a year. All over Hasselt, houses are empty and there are no buyers for them. Some houses fall into such disrepair that they are demolished. The situation is made worse by the storm disaster on 21 November 1776, which floods much of north-west Overijssel. In November 1775, it had been touch and go. The dykes had held, but the raging waters had been close at hand. At four in the morning on this 21 November, the water was already pouring over the banks of the moat and standing two feet high against the houses. In the slightly lower Nieuwstraat, the water stands three feet high. Efforts are being made with all hands to save the city centre, which has succeeded. East of Hasselt, the dykes break and the entire area up to Rouveen and Staphorst is flooded. Hasselt is an island surrounded by an area of water several kilometres wide.

Dulcken's house is bought by Grevensteijn in February 1777. He sends a letter to the magistrate a week later requesting permission to repair the house to make it habitable again. The window panes, floors and walls need to be repaired and the gutter renewed. He had wanted to tackle it earlier, but waited for the sale. Now that he has become the owner himself, he wants to get to work immediately. The wall between Rainbow Lane and his garden has fallen over and is in his garden. The fence between his garden and the court martial building also needs to be repaired. As these are town properties, he asks for permission to repair it. On 14 March, he receives the magistrate's requested permission, provided he does the repairs in consultation with carpenter and mason Baas.

The records for the 50th penny record that the house was sold by auction on 14 June. Grevensteijn buys the house for 33 guilders, a pittance of what it was worth ten years earlier.

Register of the 50th token 1777.

Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken jr

Munich

Johannes Lodewijk received his education from his father in Hasselt. When his parents move to Antwerp in 1776, he joins them. He spent the first 15 years of his life in the small town of Hasselt; now he went to the great city of Antwerp.

In Antwerp, he probably started working immediately in his father's workshop, which constantly improved his new invention. The revamped harpsichord was given the name pianoforte. How long they worked together in Antwerp is not exactly known; probably only two years. Sometime between 1777 and 1780, his father moved to Paris, where he set up another workshop.

Probably the Dulckens, father and son were very successful. Even so successful that this is noticed by Karl Theodor von der Pfalz, the Elector of Bavaria. This Karl Theodor was an important man at the time and governed a large territory in Germany. He was also in possession of the Land of Ravenstein and the Marquisate of Bergen op Zoom, and he is Duke of Gulik and Berg. So he has quite a few connections in the Netherlands. Charles Theodore is a great music lover and plays an instrument (flute) himself. He asks Johannes Lodewijk jr. to accompany him to Munich in 1779. He was only 18 at the time. So young and already recognised as a genius harpsichord maker.

Much is known about his life and work in Munich. Several articles have been written about it. Therefore, some outlines now.

In Munich in 1779, Louis entered the service of royal piano builder Johann Peter Milchmeyer, working at the court of Elector Karl Theodor, as an assistant. In his workshop, Johann Peter's responsibilities include carefully preserving, improving and renewing all the grand pianos belonging to the palace. In June 1782, Dulcken takes over Milchmeyer's office and becomes city piano maker at the age of 21. He is a true craftsman. He makes special instruments for the court and sells one pianoforte after another, not only in Munich and Bavaria, but also far beyond. In Munich, he is addressed in different ways: Johann Ludwig, Jean Louis but often just Louis.

Kurpfälzisches Museum Heidelberg

Kurfüstin Elisabeth Auguste

Keurvorstenpaar (links en rechts) en het klavier van Louis Dulcken II

Marriage

In 1799, Louis Dulcken married Sophie Lebrun and thus became part of a very musical family. His wife Sophie is the daughter of the Baden virtuoso oboist and composer Ludwig August Lebrun and of the Baden soprano and composer Franziska Danzi. Sophia is an exceptionally good pianist and composes musical pieces herself. She performs in Paris, Switzerland and Italy.

Louis Dulcken and his wife Sophie have seven children, two sons and five daughters, almost all of whom make careers as well-known musicians. By marriage to Sophie Lebrun, Louis Dulcken's house ‘for a long time forms the most interesting meeting place of the then well-educated music world in Munich’. Musicians and composers visit.

Dulcken is also doing well financially. He makes a lot of money with his unique pianofortes. Royal houses all over Europe buy his instruments. Empress Josephine of France buys two of his instruments during her visit to Munich in 1805/06 and shortly afterwards she orders a third, which they are so pleased with in Paris that it is exhibited there for a long time. In 1816, a grand piano is delivered to the Austrian Empress Carolina Augusta, a daughter of Bavarian King Maximilian I Joseph. An instrument also goes to St Petersburg.

Louis & Sophie Dulcken

Greifenberger Institut für Musikinstrumentenkunde

His work

Dulcken has developed in his long career by constantly trying new improvements. His work shows that he has been influenced by various movements.

From his father and grandfather, he learned how to make the construction of instruments optimal. His way of fixing the soundboard is typically something he brought from home. The gluing of the walls of the sound box to the bottom where the walls are first glued before starting the further construction of the fortepiano is also something he brought with him from Hasselt/ Antwerp. His father and grandfather's influence can be recognised in the choice of thickness of the various parts.

He was also influenced by Augsburg piano builder Andreas Stein and by other South German instrument builders.

Music experts tell us that Louis Dulcken is considered the most successful piano builder in Munich during his lifetime. He is praised, for example, for the quality characteristics of his instruments. They have ‘a pure sonorous tone’, keep ‘a permanent tuning’ and can mimic bassoon, harp, harmonica etc by means of a cleverly applied mechanism'. They are characterised by ‘elegant and tasteful construction’, making his instruments highly respected and welcome. In short Dulcken is genius in his method of construction. He knows how to bring out sounds from his instruments that thrill listeners.

His pianos won awards. In both 1819 and 1820, he received a medal at a major exhibition in Munich for his outstanding fortepianos.

Father Johannes Lodewijk Sr was still able to witness his son's success. He kept in touch with him from Paris and at the end of his life he also moved to Munich, where he died between 1793 and 1795.

In 1828, Louis stops working as a court piano maker. He dies in 1836; his wife Sophie in 1863.

"Dulken, (Johann Ludwig), wurde zu Amsterdam den 5. August 1761 geboren, lernte in seiner Vaterstadt, und dann in Paris von seinem Vater Klaviere, Fortepiano und dergleichen Instrumente bauen, und wurde vom Churfürsten Karl Theodor als mechanischer Klaviermacher an seinem Hofe zu München 1781 angestellt, in welcher Eigenschaft er sich noch befindet, und daselbst den 18. April 1799 die berühmte Klavierspielerinn Sophie Le Brün heirathete. Dieser Künstler erwarb sich durch seine vortreffliche Fortepiano, die einen reinen, sonoren Ton haben, eine andauernde Stimmung halten, und durch einen geschickten angebrachten Mechanismus Fagote, Harfe, Harmonika etc. nachahmen, die vom Friederici in Gera erfundene Bebung vortrefflich enhalten, u. s. w. auch sich durch eleganten und geschmackvollen Bau auszeichnen, große Celebrität, seine Instrumente sind sehr gesucht und willkommen, und finden zahlreichen Abgang nicht nur in ganz Deutschland, sondern auch in Frankreich, in der Schweiz, Italien, Rußland u. s. w." Baierisches Musik-Lexikon, 1811, p. 70

"Dulken, (Johann Ludwig), was born in Amsterdam on 5 August 1761, learned to build pianos, fortepianos and similar instruments from his father in his home town and then in Paris, and was employed by Prince Karl Theodor as a mechanical piano maker at his court in Munich in 1781, in which capacity he is still employed, where he married the famous piano player Sophie Le Brün on 18 April 1799. This artist made a name for himself with his excellent fortepianos, which have a pure, sonorous tone, keep a constant tuning, and imitate the fagote, harp, harmonica, etc. by means of a skilfully installed mechanism, excellently incorporate the tremolo invented by Friederici in Gera, and so on. etc., and are also characterised by their elegant and tasteful construction, are very popular, his instruments are much sought after and welcome, and are in great demand not only throughout Germany, but also in France, Switzerland, Italy, Russia, etc." Baierisches Musik-Lexikon, 1811, p. 70

The legacy of the Dulcken family

Around 1780, the rise of the fortepiano caused interest in the harpsichord to disappear. In fact, after 1800, many harpsichords were thrown in the rubbish or literally set on fire. Nevertheless, harpsichords have survived and are now on display in various museums.

About 15 harpsichords by Johannes Daniël Dulcken have survived but none are known by Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken (1735-1793).

By Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken (1761-1835) another 25-30 instruments are known, both harpsichords and pianofortes. They are in museums and in private hands. The earliest known fortepiano was built in the late 1780s and is in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. The youngest instruments date from the post-1830s.

Around 1980, interest in classical harpsichords increases again. People tried to precisely recreate an original Dulcken in order to produce the same tones and sounds. Since then, many harpsichords have appeared on the market that are copies of one of the Dulcken harpsichords. Advertisements also announce concerts using a (copy) Dulcken.

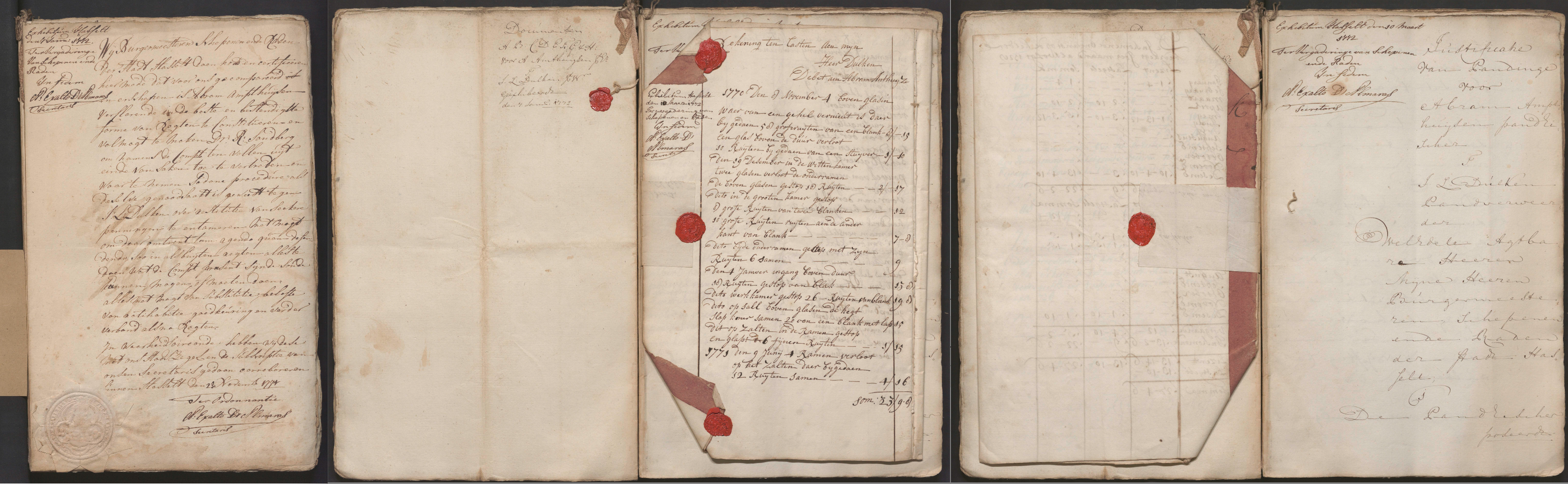

On 30 April 2024, at Collection Overijssel, a document in inv. no. NL-ZICO 0058.2. File 475 opened on which four wax seals were attached.

VIDEO

What is the story behind this?

1791 Louis Dulcken Fortepiano National Music Centre

DESCRIPTION

This grand piano was made by Jean-Louis Dulcken in Munich, Germany around 1790. There is an inscription in ink on the soundboard, discovered during a restoration in 1985, that reads “Dulchen in München.” The piano also has a spurious Stein label on the soundboard. The piano has a compass of FF-g3, Viennese action, with back checks on rail, deerskin on wood core hammers, brass and iron strings, 2 strings for each note, 2 knee levers: both damper lifters, wood frame, straight-strung, and a cherry veneer case.

LOCATION

Currently not on view

OBJECT NAME

piano

DATE MADE

1785-1790

MAKER

Dulcken, Jean-Louis

PLACE MADE

Germany: Bavaria, Munich

PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION

deerskin on wood (hammers: material)

brass and iron (strings: material)

wood (frame: material)

cherry veneer (case: material)

National Museum of American History

A ne pas confondre avec le précédent, Johannes Ludwig DULCKEN II, son fils, né en 1761 à Amsterdam. Celui-ci devint 'Mechanischer Hofklaviermacher' à Munich dès sa vingtième année, il deviendra d’ailleurs le Facteur de piano de Sa Majesté le roi de Bavière en 1808. La dernière mention de son existence date de 1835 et l’entreprise « DULCKEN et Fils » est attestée dès 1830. (1820 - "Bei der disjährigen, durch den polytechnischen Verein für: Baiern zu München veranstalteten Industrie- und Gewerbsausstellung, haben folgende Konkurrenten die von dem Verein gestiftete Medaille erhalten: [...] Der Instrumentenmacher Dülken zu München, für die Vorzüglichkeit seiner Fortepianos." Allgemeine Zeitung München, 06/01/1820, p. 23

Foundation Musick's Monument

Foundation Musick's Monument