Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken

Master Harpsichord Builder

Hasselt 1762-1776

Henk Poelarends © 2024

in cooperation with Hans Meijer

Introduction

This story is about Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken sr. and his son Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken jr. Short biographies of both can be found on the internet as they belong to a famous family of harpsichord and organ builders. These descriptions reveal that the Dulcken family left Amsterdam around 1762 and only to reappear in Antwerp around 1780. A gap of more than 15 years. Research in the old archives of the City of Hasselt shows that members of this famous family lived in Hasselt's Nieuwstraat at that time. There, they built organs and harpsichords that were sold throughout the Netherlands. This story is about them and thus fills the gap in their life description.

Who is Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken?

INFO IN HET GULDEN CRUIJS. MUNTSTRAAT 26

Maastricht

Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken was baptised at St Janskerk in Maastricht on 15 April 1735 as the eldest son in the family of Johannes Daniël Dulcken and Susanna Maria Knopffell.

His father was born in Wingeshausen (D) on 21 April 1706. His mother was born around 1706 in Sankt Goar on the Rhine.

The young family is in money trouble in Maastricht. On 1 March 1736, Daniel borrows 300 guilders at 5% interest from his cousin Gerhart Prescher. The promissory note was written by Daniël in High German and was later translated into Dutch in connection with the ensuing trial.

In October 1736, they moved to a house located at De Munt called Het Gulde Cruijs. The house is located between ‘Het Gulden Hooft’ and ‘Den Swerten Rave’. They rent the house from Maria Catharina Bijen for a period of six years. His brother Jan Christiaan Dulcken acts as guarantor. In this large property, Daniel and his wife run a grocery shop, a gruttery. How much time he spends building harpsichords is not clear; in the deed he is called a merchant. During 1737, Daniel borrows 600 guilders from the widow of mayor Hesselt van Dinter. It then turns out that he earns too little to pay off all his debts. Around the turn of 1737/38, he leaves Maastricht for Antwerp. Johannes Lodewijk is not yet three years old when they arrive in Antwerp. Meanwhile, the house at De Munt is no longer occupied, but it is not empty. Daniel has left behind much of his furniture and shop inventory. Then the creditors report to the magistrate of Maastricht. The latter appoints Johan Guichard as curator over ‘the desolate estate of the absent Jan Daniël Dulcken’. A public announcement appears on 17 June 1738; anyone who thinks they are entitled to something from the bankrupt estate must come forward. Several people appear: family Bijen, brother and sister, report that Dulcken owes them nine months of rent arrears, totalling 138 gulden.

Cousin Gerhart reports that he still owes 225 guilders and widow Hesselt van Dinter receives 600 guilders. A merchant from Amsterdam, Gerard Katers, also reports being entitled to 410 guilders, as costs of goods and for valuation costs.

On 20 June 1738, they enter the Gulden Cruijs to value all goods.

The valuation report shows that there are many tables and chairs as well as a ‘stoeltien and a loopkorf’ (for Johannes Lodewijk?) In the shop there are a counter, some safes, a large iron balance with six scales, a small-sized balance, 50-pound weights, tin measuring cups and a tobacco mill. Also many barrels, wooden boxes, baskets, oil tubs and barrels of tobacco, etc. One also finds two violins without strings and a trumpet. It is clear that Daniel took everything related to the construction of harpsichords with him to Antwerp.

Historisch Centrum Limburg, inv. nr. 4573

The young family moves to Antwerp in 1738 in poverty. Debts incurred in Maastricht are on their necks. Time and again they receive letters from the trustee in Maastricht and each time Daniel has to answer them. This lasts until the middle of 1740. How the debt is repaid is not clear.

VIDEO BANKRUPTCY

Antwerp

Antwerp

Antwerp in the 17th century is the city where leading harpsichords are built by the Ruckers family. Over a period of 50 years, they made more than 3,000 harpsichords, 100 of which can still be found in museums today. Their harpsichords differ from all instruments made until then because of their timbre, construction and design. Their manner became the standard for much of Europe.

When young Johannes Lodewijk arrives in Antwerp a hundred years later with his father, mother and little sister, they continue the tradition of the Ruckers family.

A brilliant harpsichord maker, Father Dulcken has been called the most esteemed Flemish harpsichord maker of the 18th century. They probably got out of debt quickly, as the impression is that they were already in good spirits by 1747.

The Dulcken family joins a small Reformed church in Antwerp in 1740: the Olijfberg, where Johannes Diepelius is pastor. In that Roman Catholic environment, the congregation forms ‘a church under the cross’ and are tolerated when they do not cause offence. This means that the small congregation often meets at the home of one of the members on Sunday mornings. This must surely have impressed young John Louis. In the church, his father becomes an elder and thus directs all church affairs. Johannes Daniël Dulcken is a seen person in Antwerp.

The workshop is located in Hopland, not far from the Jodestraat where Ruckers once worked. Besides building harpsichords, he also sells glassware for a glass factory in Ykenvliet.

Dulcken offers his harpsichords in a large region. In 1750, he even went to England to sell two of his harpsichords there. Dulcken made harpsichords with single and double manuals that often had a range of five octaves and three stops: two 8‘ and one 4’. He decorated the soundboard with flowers and carved his initials in the rose.

Johannes Daniel Dulcken 1755 - Das MK & G Museum Hamburg

About ten harpsichords by his hand have survived.

Joannes Daniel Dulcken 1745 - Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Sammlung alter Musikinstrumente, 726

Johannes Lodewijk (call sign Louis) and also his seven years younger brother Joannes receive a thorough education from their father. Not only do they learn how the Ruckers built harpsichords, but father Dulcken develops harpsichords with even more beautiful sounds and with even better construction.

In 1755, Louis, aged 20, leaves to go his own way. He and his father disagree on the direction of the business. One of his first assignments is the restoration of an organ in the Brabant town of De Leur. There, together with another organ builder, he has to take the organ apart, replace some parts, repair and clean others. All pipes also have to be retuned. All in all, that takes two months of work. For this they receive 125 guilders with board, lodging and a good bottle of wine each day. After finishing his work in De Leur, he left for Amsterdam.

In March 1755, he is registered as a member in the Amsterdam Reformed Church. Nevertheless, he decides to leave Amsterdam and settle in Kleve. But before that happens, he meets Catharina Koning in Amsterdam. He decides to stay in Amsterdam to establish a business there.

The young couple married on 7 May 1756. His father has to give permission for this because he is not yet of age.

Immediately after this marriage, it is arranged by will that the youngest son Joannes, upon father's death, takes over the business. When his father dies two years later, mother takes over the business because Joannes is still a minor.

Meanwhile, the eldest daughter, Joanna Henriëtta Dulcken married Johann Hermann Faber, , a well-known painter. In 1763, the mother petitioned the magistrate of Antwerp to grant her permission to move to Brussels. There she sees more opportunities to continue the harpsichord-making workshop together with her son-in-law. She also asks permission to dispose of her young children's money.

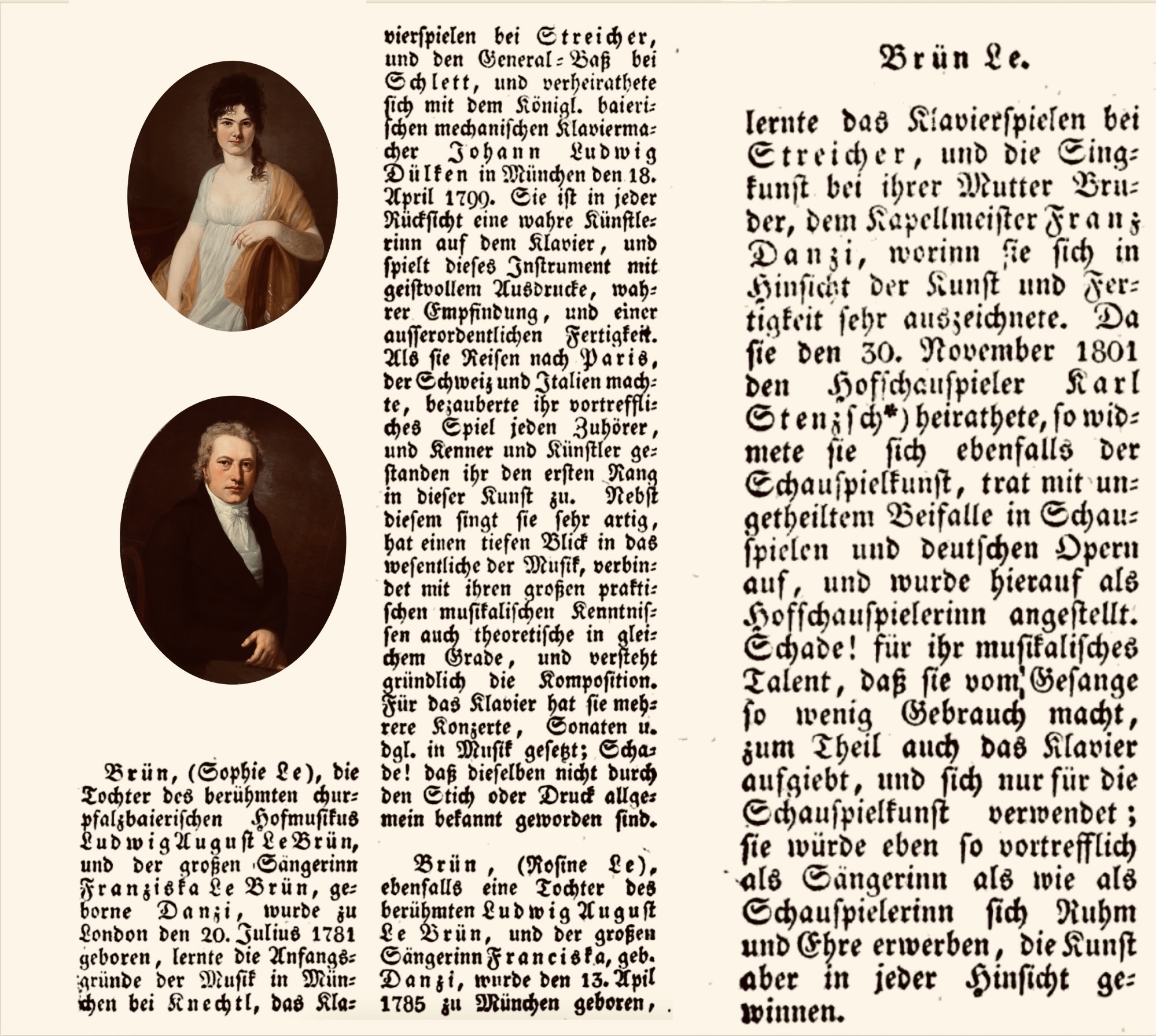

A painting, painted in 1764 by the painter Jan Joseph Horemans (1714-1790), hangs in the Snijders&Rockoxhuis in Antwerp. It is believed to depict the Dulcken family. On the harpsichord, the maker's signature ‘DUL [...] 1764’ is partially visible, most probably Dulcken. This instrument was probably made by Joannes Daniël Dulcken (1706-1757) and later signed by his son Joannes (1742-1775). In 1764, the family moved to Brussels. We see Joanna Henriette and Maria Sophia in the foreground, Joannes on the cello, Joanna, the youngest daughter in the middle. Behind them Jean Herman Faber who is married to the eldest daughter. Is a messenger coming to bring word that permission to move to Brussels has been received?

Johannes Lodewijk has already left for Amsterdam, with Joannes later leaving Brussels to set up a business in Amsterdam.

Snijders & Rockoxhuis

Signed and dated lower left: J Horemans 1764 on the floor

Joanna Henrietta Dulcken 10-02-1737 & Jean Herman Faber 1734

Maria Sophia Dulcken 26-01-1740 - †17 Januari 1805

Joannes Dulcken 10-09-1742

Joanna Eliezabetha 2-2-1747

Amsterdam

Johannes Lodewijk (Louis) Dulcken built up a thriving business in Amsterdam. He and his wife Catharina Koning live in the Nes verbij de kuiperssteeg with a workshop south of the Kathuysers Kerkhof, near the Weduwe Hofje, and from there Dulcken sells his instruments.

GEVELSTEEN KUIPERSSTEEG

His first advertisement appears in the Amsterdam Courant of 18 May 1756. He presents himself as Mr Louis Dulcken, organ maker, and he offers a Staart-Clavecimbel with long keyboard, an authentic Hans Ruckers. Three months later, he presents himself as Mr. Organ and Harpsichord Maker.

The harpsichord played an important role in musical life in the 17th and 18th centuries. Well-known composers such as Bach, Handel and Vivaldi play on this instrument and compose their pieces of music on it.

Many wealthy people have a harpsichord in their living room. Dulcken will therefore have had this group of wealthy citizens as customers.

In a harpsichord, the sound is produced by vibrating the strings. When you press a key, a goose pin or a leather plectrum passes along one of the strings. It makes a plucking sound like a harp, but it is not possible to play loud or soft. The instrument has a wooden sound box, while the strings are made of iron, brass or bronze. The harpsichord is about 180 cm long, 81 cm wide and 91 cm high. Advertisements often refer to it as a ‘Tail Harpsichord’. This is a reference to the long wing-shaped shape that distinguishes the instrument from virginals with a rectangular shape, which are also usually smaller. The instrument has a tone range of at least four octaves.

In August 1756, he offers for sale out of hand a ‘superbe (excellent) King's Cabinet Organ, whose equal has never been seen here’. He also has for sale a Tail Harpsichord by Andreas Ruckers with three stops and a long Clavier. Apparently, the sale is not going well because in December 1756 he offers them for sale again. He is keen to get rid of them as he plans to move.

The cabinet organ belongs to the group of organs that find a place in the living room. It originated from a cabinet on high legs that was specially made for storing small valuables. Behind the two doors, which are often beautifully painted, is a large number of drawers. In the late 17th century, the cabinet becomes larger and larger drawers are added. In the 18th century, the small drawers behind the doors were removed and a complete organ with bellows and keyboard was built inside. This is a typical Dutch form for a house organ.

The Cabinet organ built by Dulcken is so large that with little effort it could also be used in a church. In May 1757, he still advertises it. He now also gives more details about the organ: Capitale Cabinet Orgel 8 feet present, 4 feet Octaaff, 7 and 1 half stops. On 15 September 1757, he indicates that from then on organs and harpsichords are always for sale with him.

Probably this ‘Koninglyk Cabinet Organ’ was sold to merchant Jacob de Clerq (1710-1777). He lived in a fine canal house, Keizersgracht 187, with a small hall in which he had a large house organ installed. The organ retained its purpose until it was sold in 1818 to the Hervormde Gemeente in Jutphaas, where it continued to serve as the Dulcken organ until 1972.

These ads show that Johannes Lodewijk also devoted himself to building small and large organs. These ads also show that he sells hundred-year-old Ruckers. This means that when building his harpsichords, he takes the famous Ruckers as an example. To achieve greater production, he employs one or more servants. When building his organs, he constantly makes improvements and embellishments. In April 1759, for instance, he advertises ‘a magnificq new-fashioned Cabinet-Orgel, being very comodely made with outgoing Clavier and provided with the principal Registers &c’.

Louis Dulcken followed trends of the time and made sure his organs featured the latest modifications. The question is whether he makes the cabinet for his organs himself or buys them from skilled cabinet makers.

Another development Dulcken is involved in is making very small organs. These small organs are built in a desk and are therefore called desk organs. The idea of a desk organ comes from England. To build this instrument, you have to be very technically skilled because you have to place the organ pipes in a limited space. They cannot stand, but have to lie down. One suspects that Dulcken was one of the first organ builders in Amsterdam to master this art, thus attracting attention.

On 18 November 1759, he advertises for the last time in the Amsterdamse Courant. He offers ‘some Staart-Clavecimbaals of such own work, as double with 4 Registers and 5 octaves, as some with 3 Registers and long Clavier, among others an extra kleyn comodieus Staartstukje with 2 Regist, edog lang Clavier &c’. By the looks of it, he is holding clearance.

From the marriage of Johannes Lodewijk and Catharina, four children are born in Amsterdam. The last one is named after his father. Johannes Lodewijk jr. is baptised on 9 August 1761 in the Gereformeerde Kerk in Amsterdam.

For unknown reasons, the family left Amsterdam and crossed the Zuiderzee by ferry and arrived in Hasselt in early 1762. The fifth child , Overijssel, is born and baptised in the Gereformeerde Kerk on 13 May 1763.

Living and working in Hasselt

Hasselt around 1760

Hasselt, the city on the Zwarte Water, had about 1,100 inhabitants in 1760.

Hasselt has a rich history as a fortified town with many privileges including its own jurisdiction.

Nicolaes van Galen - Justice of William the Good - Old Town Hall HASSELT Overijssel

Via the waters of the Zuiderzee, there are connections to Amsterdam, Hoorn and Enkhuizen. Trade is an important source of income but Hasselt's heyday was a hundred years earlier. Hasselt has become a poor city and this is clearly evident. Thirty per cent of its inhabitants are plunged into poverty and can only survive with help from the poor. Collection boxes are hung at various places in Hasselt where wealthy residents can deposit donations while a door-to-door collection is held four times a year. The average age is low and infant mortality is high.

Houses are under-maintained and many are empty. Residents with money have sought refuge elsewhere and the number of artisans has fallen sharply over time. The manners between the residents have become rough, there is discord in the city administration and quarrels between the members of the magistrate are frequent. Remarkably, in 1762 another death sentence was carried out in the market square near the town hall. A man accused of culpable homicide was beheaded with a sword in front of the crowds of citizens. In early 1762, Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken arrived in Hasselt with his wife and three small children.

The house

The Dulcken family goes to live in Hasselt at the corner of Nieuwstraat and Regenboogsteeg. There, there are four properties ( nos 1 , 2, 3 and 4 on the drawing) that have changed hands in the last decade.

They belonged to the wealthy Arnoldina van Benthem, who lived here until her death in 1751. She owned many houses in good standing in Hasselt besides this house. Her brothers were mayors in Hasselt and from her will we know how wealthy she was. She was unmarried and her nephew Frederik Hendrik van Benthem inherited her property.

After the latter died on 12 May 1754, his heirs were given a large number of properties, barns and pieces of land. As a result, the four properties mentioned above come into the joint ownership of Messrs Daniel and Hendrik van Hecht, wealthy merchants from Amsterdam, (2, 3 and 4)

They belonged to the wealthy Arnoldina van Benthem who lived here until and Mrs Van Noorda (1) who all put several properties up for sale. The corner property (1) is bought in 1755 by Tede de Vries for 110 guilders, the second property (2) comes into the hands of Hendrik van Hecht and has a sales value of 430 guilders. He will rent out the property. The third and fourth properties (3,4) are bought by Mr Van Guldener, who immediately resells them to the civil war council for 265 guilders per property. The four properties have a common garden. (5)

Louis Dulcken rents the premises from De Vries (1) and from Van Hecht (2). Because these properties were previously owned by one owner, they are not strictly separated. When the city of Hasselt collects ground rent on these properties, it is considered one property with two owners.

What this large property looked like we know from several documents.

- When Hendrik van Hecht took over his brother's part of the property in 1755, it is described as a ‘large house’.

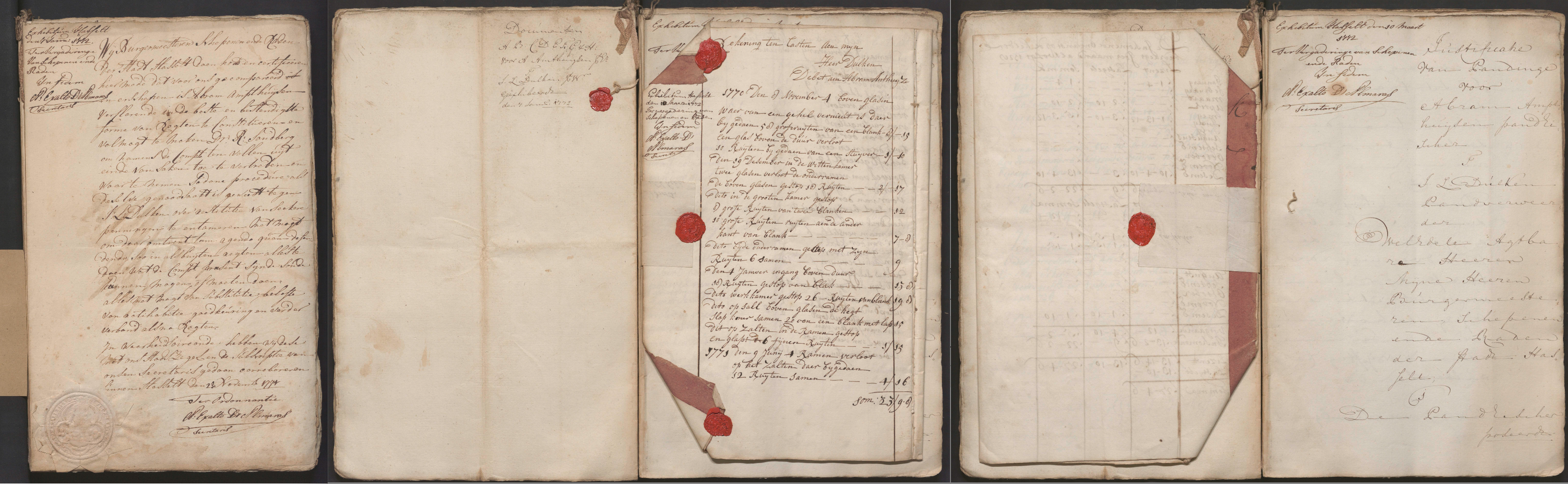

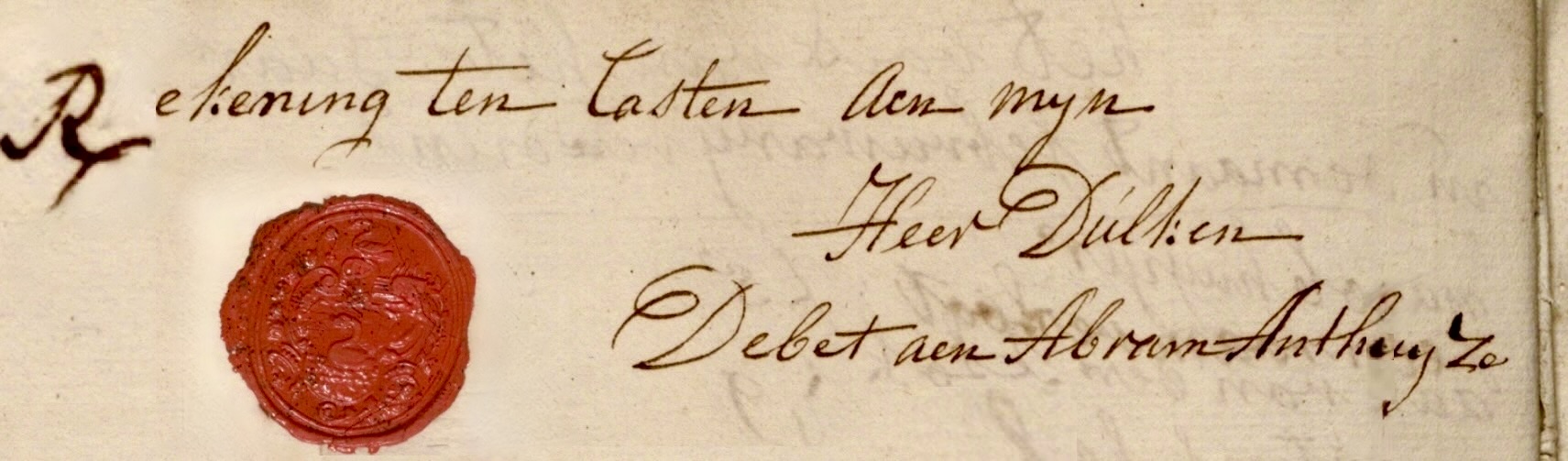

- Dulcken receives a bill from the glazier Abraham Anthuyzen in 1771 after he set glass in the Wittenkamer, in the great room, in a study and in the servant's bedroom, upstairs, for two years. This involved both coloured stained glass and clear glass.

- The double property is sold in 1851 as a very antique, solid, strong, well-maintained dwelling house. It has a large hall, several spacious downstairs and upstairs rooms, some of which possess stained-glass windows. There are a large attic, a kitchen and a cellar. From all this, you get the impression that we are dealing with a stately mansion.

Remarkably, the painter Cornelis Springer made a beautiful painting of this part of Nieuwstraat in 1863. Here we see Nieuwstraat with a view of the town hall and the tower of the Hervormde Kerk. We also see daily life on the street that is not so different from life at the time Dulcken lived there.

Springer made the painting just before all four adjacent properties were demolished around 1863-65. On the left, we see the two monumental premises of the court martial, the second of which has a beautiful front door. (3) In this building, the ‘manly civilian court martial’ meets. The court-martial directs the night guards who ensure order and peace in the night hours. The building is also where the guilds often meet.

To the right of this stood the two Dulcken properties. By then, these had already been demolished to make way for a church. To fill the empty space, Springer placed a wall and pretended there was a large tree in the garden behind it. In 1755, even more money was paid for the property where Dulcken will live than for the court martial's premises. This indicates how big Dulcken's property was.

Considering the other, still existing, houses in the street, Louis Dulcken's premises (2) could have looked like the first house on the left in the painting. Building (1), on the corner with Rainbow Street is much smaller. Perhaps it served as accommodation for Mrs Arnoldina van Benthem's maids.

Dulcken will live in premises 1 and 2 with his wife and three children. There is also room for a servant who, as usual, finds a place to sleep upstairs in the attic.

This is where Johan Daniël Dulcken is born and baptised on Sunday 13 May 1763 in the Reformed Church a hundred metres away. The little boy is named after his famous grandfather.

Between 1762 and 1769

The young family brings three small children with them to Hasselt:

Susan Maria, just five years old, Daniël Lodewijk, two years old and Johan Lodewijk jr. aged a few months. Dulcken and his wife are both around 27 years old.

One might wonder why Dulcken moves to Hasselt. He grew up in Antwerp and worked in Amsterdam for years; thriving cities with many potential clients. He dealt with rich influential people. Does his way of life, his dealings with fellow city-dwellers fit with Hasselt's impoverished population? Everything shows the distance between Dulcken and his new locals. When one of the children dies, it is noted in the burial register as: child of Mr Dulcken, while for all other children who died, the father's first name is mentioned. The same happens in 1767 when registering the head money. One notes ‘The Lord’ Dulken while all the neighbours are listed with their first names.

In Hasselt, Louis goes to work as an organ and harpsichord builder. He set up a workshop and workshop in the building on Nieuwstraat.

To build a harpsichord, you need materials. Louis probably got that from Amsterdam. There is a ferry service from Hasselt to Amsterdam and it brings goods and people from one place to another every day. The wood for the instruments is first stored to dry properly.

Children were also born in Hasselt: Johan Daniël is baptised 13 May 1763; and on 24 April 1764 the burial register records that a child of Mr Dulcken is buried. On 22 July 1764 Johan Daniel is baptised (another son named after his grandfather) and on 16 March 1766 Johannes Ferdinandus. On 4 September 1766, Dulcken had to carry another child to the grave. Infant mortality in Hasselt is high because of all kinds of childhood diseases for which there are no medicines. Only when someone has survived all childhood diseases is there hope that he will reach an adult age.

Drawing of the Reformed Church Hasselt after lightning struck the tower. On the right, the cemetery where Dulcken's children are buried.

Problems

Meanwhile, Dulcken is trying to sell the harpsichords. From 1760 onwards, we find only a limited number of advertisements in the newspapers. For instance, he is in Middelburg in the summer of 1765. The advertisement of 17 August says that ‘J.L. Dulcken, Mr. Orgel- en Clavecimbalmaker, has arrived here in Middelburg, and has brought along two magnifique Clavecimbals, which are presented for sale out of hand’. He stayed in Den Helm, at the home of J.H. Callovius, where he explained his instruments in the morning and afternoon.

In 1766, he went to Leeuwarden with his instruments. There, on 5 April, he is announced as Mr. Orgel- en Clavecimbelmaker from Hasselt. Every day he can be found in the Vergulde Wagentie on the Schapenmarkt in Leeuwarden with a magnificent Staart-Clavecimbel with three stops he made himself. This is the only time an advertisement mentions Hasselt as his place of residence. Apparently, his name as an instrument maker is so widely known that there is no need to add who he is.

Nu ingemetseld Pijlsteeg Leeuwarden

In October 1766, Dulcken bought a house with court and yard in Hofstraat for 35 guilders from Roelof Coppens. He probably wanted to set up a workshop there. Dulcken then changes his mind and sells the house back to Coppens a few weeks later.

An entry from Wolvega is known in 1767. He is asked to repair the organ of the St-Maria Magdalena church. It is a major repair and Dulcken asks 153 guilders for it. He is then staying with kastelein Claas Hansen Kopffer. Every time he goes back to Hasselt, he is fetched and brought by Jan Sickinga. The innkeeper sent a bill for 88 carolus guilders as accommodation expenses.

The big difference with his period in Amsterdam is that Dulcken then sold harpsichords and organs from his workshop. Now he travels all over the Netherlands to sell them. This takes much more time; time he cannot spend making his instruments. Probably the work of his servant, Ernst Johan Tappe, continues in the workshop, but the costs are higher.

Later, he even has three servants who build one harpsichord after another in the workshop. It turns out that the proceeds from his organs and harpsichords are not enough to cover expenses at home. Over the years, he incurs debts and has to borrow money.

When he comes home from travelling, he promises to pay the debts as soon as possible, but often fails to do so. Godfried Scheffer, harpsichord maker in Amsterdam demands 200 guilders from Dulcken in August 1763 because of an unrepaid loan, and Siegwriet Markard from Amsterdam demands back a keyboard that belongs to him but is still at Dulcken's workshop.

Thus, he cannot pay the bill of Wijnverkoper Cornelis Warneke of Amsterdam for wines he delivered in 1764 and 1765. In October 1766, Warneke goes to the Hasselter magistrate to enforce payment. Dulcken resolves this by immediately paying 25 carolusgulden and promising to remit a subsequent amount each month.

The same happens to his servant Johan Ernst Tappe, who came from Germany. He works in his workshop in the year 1765 and part of 1766. The wage is 30 pennies a week. Tappe went to Dulcken's door several times, and even received 1.12 once. Since he has also borrowed 4 guilders from Dulcken in addition, he demands the sum of 84.80 through the magistrate. If he does not receive money now, he demands confiscation of goods (pledging) so that through the sale of these goods he can get his money. He also no longer wishes to work for Dulcken. Again, Dulcken comes up with 25 guilders as a pledge so the seizure does not go through.

A year later, he cannot pay for the peat delivered in winter. Time and again, he has to ask for a delay in payment. People no longer trust him to keep his promises. They are angry and stories circulate about him. He is called names and scolded in the streets.

Would Dulcken remember his father Daniel's situation? How the latter experienced the same thing in Maastricht 35 years ago? How difficult it is to make a living as a harpsichord maker?

Being treated with contempt is part of it. So too on 6 February 1767. Dulcken was sitting in innkeeper Willem Buysman's inn when he was attacked by Paul van Veen, manager of inn De Herderin. The latter accuses Dulcken of owing him 40 guilders. He grabs Dulcken by his coat and shouts that he is a cheat, knave, scoundrel and jackal and that he is out to cheat people. Paul shouts so loudly that this is noticed outside by the city guards. These step inside to see what is going on. Dulcken, with the help of Mr Grevensteijn, files a report with the magistrate for insult. He feels his honour and reputation have been violated. The city guards are called as witnesses. Dulcken first makes an attempt to settle the matter amicably through the mediation of ‘two good men’. Paul van Veen refuses, after which Dulcken's lawyer sues him, claiming 100 ducats in damages. This suit continues until at least March 1768.

Since the sale of harpsichords is unlikely to go smoothly, Dulcken has to borrow money. On 12 February, for instance, he borrows 50 guilders from Abraham Amthuijsen; a glazier/painter with whom Dulcken is on good terms. On 15 September, he borrows another 200 gulden from him.

On 19 October 1767, Dulcken goes to the Herderin, the inn on the corner of Markt and Hoogstraat, to pay Van Veen the forty ducats. In the taproom, he notices that the attitude of several attendees is downright hostile. ‘Break his legs’ is shouted. Dulcken asks for a light for his pipe and then quickly goes to the antechamber where the counter stands to hand over the money to Van Veen's wife. In the corridor, he is chased by Joan van der Meulen, a young man who has scolded him twice in the street recently. Joan shouts something at him, after which Dulcken turns halfway around. Joan then punches him in the face with a full fist. Dulcken falls against the counter after which Joan punches him some more. Joan's father approaches Dulcken's call for help and pulls his son away from him. With a bloodied face, beaten black and blue, Dulcken leaves the inn. He has to seek treatment from the surgeon and cannot work for a fortnight. Again, his lawyers file a complaint with the magistrate; witnesses are heard and 100 ducats of damages are again demanded. Six months later, Joan still protests against this, saying Dulcken started. Unfortunately, many records are missing between 1769 - 1770 so it is not known how this ended. But April/May 1768 marks the absolute low point for Dulcken.

1768

The year 1768 begins nicely in the Dulcken family. On 13 January 1768, a son is born whom they name Ferdinandus. Unfortunately, on 12 February 1768, Louis and Catharina stand by their child's grave. Again death strikes this family.

Council house in Hasselt before 1900.

On 26 April, the town hall was buzzing with activity. In the early morning hours, lawyer Waterham, with the help of the strong arm, seized two harpsichords from Dulcken and brought them to the town hall. This spread like wildfire through Hasselt. Soon A. Breman reports with a bill for Dulcken of 10 guilders and 7 pennies. A little later, lieutenant Runhard and commander Egbert Heisman of the manly court martial appear with a bill for 25 guilders and 10 pennies. They too want to share in the proceeds from the sale of the harpsichords. Next comes Tede de Vries requesting that the harpsichords be returned quickly, as he has just bought them and also already paid for them. He shows a receipt to reinforce his request. The magistrate is utterly confused.

On 29 April, Dulcken has to appear at the town hall to confirm that he has debts with Tede de Vries, landlord of the small property.

The total amount has reached 513 guilders and 17 pennies. Louis Dulcken confirms to the magistrate that these are indeed his debts.

In addition, he has the following debts:

A debt of 120 guilders and 10 pennies with Albert Berend van der Werff for delivered animals for slaughter and a pig (probably spread over several years)

A debt of 25 guilders and 10 cents to the court martial for not paying garden rent and drum money for two years

A debt of 54 guilders and 4 pennies to R. Metelenkamp for delivered wood for building harpsichords

But the money runs out in no time. At the end of September, Dulcken knocks on Abraham Amthuijzen's door again. He has no money to buy peat. Abraham lends him 30 guilders, but as he does not have that money himself either, he pledges goods to the bank of loan. And on 14 November, Dulcken buys a ‘slagtbeest’ from Salomon Abrahams for 73.00. Unable to pay that, Amthuijzen stands surety. Thus the debts quickly mount up.

The years 1769 - 1772

House bought on Nieuwstraat

In December 1768, Johannes was born and baptised in the Reformed Church on Boxing Day. They give him the call sign Jan.

On 18 March 1769, Abraham Amthuijzen comes to Dulcken's house. Abraham thinks Dulcken should start paying off his debts. It now appears that no written record of the debts Dulcken has incurred has ever been made. Amthuijzen asks for a written acknowledgement of debt. And he gets it, signed by ‘J.L. Dulcken and his houijsvrouw Catriena Koning’. The promissory note states that they have borrowed 250 guilders and will repay 50 guilders each year in July, starting in July 1769. In addition, Dulcken will also pay 4% interest on the outstanding amount.

On 23 March 1769, Dulcken bought the small property on Nieuwstraat from Tede de Vries, his landlord, for 400 guilders. A hefty sum when you consider that De Vries had bought this property 14 years earlier for 100 guilders. However, documents show that from the time of purchase, Dulcken also owned the large property next door. He acts as owner and, precisely because of this, comes into conflict with the neighbours.

Dulcken's mother

In spring 1769, Susanna Maria Dulcken, Louis' mother, came to live in Hasselt. She is the widow of Johan Daniël Dulcken and had been living in Brussels for the last few years. On 7 August, she is registered as a member of the Reformed Church.

She moves in with her son and daughter-in-law.

More changes take place. Dulcken buys a property on Hofstraat, probably intended to expand his workshop. It is part of the house. The other half is owned by Klaas Admiraal, who has a painting and glazing business there. Dulcken has the house on Nieuwstraat refurbished by glazier Amthuyzen. It is possible that the house had been neglected while being rented out. It may also have been damaged by an autumn storm, as the adjacent premises of the court martial are being fitted with new windows by Klaas Admiraal at the same time. Windows are being replaced in several places. Some are stained-glass windows and others are windows that will have clear glass. The account gives a good idea of the layout of the house.

In the spring of 1770, Dulcken spent some time in Groningen. According to an advertisement of 6 April in the Opregte Groninger Courant, Mr J.L. Dulcken is staying at the lodge ‘het wapen van Stad en Lande’ and offers a superbe Staart-Clavecimbel with double keyboards and four stops, for sale out of hand. Dulcken so the newspaper writes has already sold far more than a hundred of these instruments in the Low Countries and they are used at most and principal concerts. The harpsichord is particularly strong and pleasant in tone.

Disagreement around the garden

Documents concerning J.L. Dulken's request to Ridderschap en Steden to obtain a surrogate address in his case against the civil war council over the erection of a fence due to the partiality of the Hasselt city court,1770-1772.

Documents: J.L. Dulken plaintiff against H. Bode, as president of the civil court of bridges in Hasselt defendant demand to remove a fence placed by the defendant on land belonging to the plaintiff by the plaintiff from a resolution of the Hasselt city court concerning this case, appealed to the Deventer city court (1771-1773)

Behind Dulcken's house and the adjacent premises of the court martial is a shared large garden. The separation between his garden and that of the court martial is cordoned off with a few posts. Since Dulcken has only a small garden behind his property, he rents part of the neighbour's garden, which he uses as a vegetable garden. During 1770, Dulcken put several stakes on the property boundary, to the displeasure of the court-martial, which finds that Dulcken is taking possession of a piece of his garden. The court-martial claims that the property division ran differently in the past and demands that Dulcken just has to prove that he is entitled to that piece of garden.

On 4 September 1770, Dulcken seeks the help of the verwalter high sheriff Grevensteijn. B. Van Hattum is also called in as a lawyer and together they file a complaint with the magistrate. The same day, Dulcken is summoned to court-martial. He is accused of engaging in land grabbing. Dulcken replies that he can prove that the separation as he has stated is the real separation. When the court-martial led by Colonel Bode meets the same evening to discuss the matter, Lieutenant Van Zuijlen and ensign Exalto D’Almeras are appointed as his representatives. The latter is secretary to the magistrate.

A witness hearing takes place four days later. Mr Grevensteijn, as verwalter hoogschout, in the presence of two keurnoten, members of the magistrate, interrogates the previous ‘owner’ of the martial property, cornet H. Guldener. The latter has to admit that the boundary drawn by Dulcken is the one indicated in 1755 when the property was sold.

On 10 September, the court-martial puts up a fence at the spot where he believes the separation between the gardens runs. The magistrate does not want to take up Dulcken's complaint until Dulcken comes up with the contract of sale. But Dulcken is busy selling harpsichords. He is in Groningen for several weeks. During his absence, his servants continue to work in the workshop, building one harpsichord after another.

On 15 April 1771, Dulcken makes a second attempt and sends a detailed complaint to the magistrate. The latter forwards the complaint to Colonel Bode of the court martial. The court-martial meets a week later and decides to give the two members concerned all rights to deal with the matter on behalf of the court-martial. The magistrate is informed of this decision. Dulcken is informed that he must first come up with the contract of sale before justice can be done.

Grevensteijn and Van Hattum now want to act quickly. On 1 May, Van Hattum meets one of the mayors in the Market Square and asks if a meeting can be held in the afternoon so that Dulcken can explain his complaint orally. The mayor opposes this. A week later, Grevensteijn sends a letter to the deputies of the Knights and Cities, the States of Overijssel. Grevensteijn is verwalter hoogschout and in that function can appeal to the Ridderschap en Steden, requesting justice in this conflict. The case is filed with the City Court of Deventer. Lawyer Van Hattum writes a note entitled: ‘Grieven van Appel en nulliteiten’ in which he explains the situation. He calls the magistrate partisan and biased. He disagrees that Dulcken has not been given a chance to defend himself because the magistrate refuses to receive him. The magistrate takes sides ‘without allowing him to bring his interests against it. ‘ t which, however, is not refused to the smartest evildoer’. It is unheard of for a judge to administer justice without questioning. Van Hattum cites an example from the Bible to reinforce his words. The Sovereign of all Sovereigns and Judge of the whole earth, who executes justice and before whose eyes everything is naked and clear, has substantiated this in his very first judgment (Genesis 3) with his most holy example, and it will also be substantiated in the last judgment at the last day' (Matth. 12 verse 36). The Deventer city court asked the magistrate for clarification.

Van Hattum needs 12 pages to put the appeal on paper. Advocate Sandberg, who writes an answer to this appeal on behalf of the magistrate, needs 120 pages. He describes in detail the situation that arose. The verwalter high sheriff had no right to appeal to the States. The city of Hasselt has its own legal order and this must not be undermined. With numerous Latin law texts and examples from the past, he tries to prove that this appeal is based on nothing. His final conclusion is that the City of Deventer should return the appeal without hearing it. After that, the trial is at a standstill for a year and a half. The magistrate does not reply, nor are any letters from Grevensteijn known. Dulcken and Grevensteijn do appear regularly at the magistrate's meeting to keep the case warm, but to no avail. It was not until mid-1772 that things started moving again.

Dulcken does not let all this put him off. He re-establishes his vegetable garden in spring and plants summer vegetables.

On 5 July 1771, the court martial meets to discuss Dulcken's work in his backyard. The colonel brings to the meeting: ‘that L Dulcken had planted the land belonging to the court-martial's hoff with cabbage plants’. The lawyer advises the cabbage plants that: ‘planted on the ground of the court-martial will be grubbed out again’. SEE SCAN After that, another line will be drawn between the two beacons. If there are still cabbage plants in the wrong place, they will be pulled out.

The sovereign Hasselter city council.

The magistrate in Hasselt consists of four mayors and four councils. Every month there is a law day on which two mayors administer justice. They make use of a city servant, a messenger, also known as a rod bearer, to deliver summonses to citizens who have to appear in court. As a sign of dignity, the rod-bearer wears a magnificent necklace.

Unintentionally, Dulcken ends up in a conflict between the magistrate of Hasselt and the Ridderschap en Steden, the States of Overijssel. The magistrate resents Dulcken and Grevensteijn for appealing to the States. After all, Hasselt claims full autonomous justice. Independently, the magistrate can administer justice in civil and criminal matters. There is no right of appeal. Even in ecclesiastical matters, the magistrate has power and influence. One of the mayors is always an elder and even the appointment of elders and pastors needs the magistrate's approval. Thus Exalto D’Almeras, the secretary of the city council, is also an elder in the church and an ensign in the court martial.

Protecting his rights, the magistrate reproaches the States for acceding to Dulcken's request for justice. He demands that they stop doing so and send the bill for work to Dulcken. This is also why it takes so long to send a reply to the States. They do not recognise the intervention of the States.

De ketting van de roedendrager.

Grevensteijn

Abraham Ursinus Grevensteijn plays an important role in the life of Louis Dulcken. Born on 12 October 1707 in Leeuwarden to a family of ministers and medics, he became one of the mayors of Hasselt in 1733. He then became verwalter hoogschout of Hasselt and the Hasselt office. A verwalter hoogschout is appointed by the States of Overijssel. The magistrate is appointed by the most influential families within Hasselt, who shove the best jobs at each other. There are also close family ties between the members of the court martial and the magistrate.

Court martial

The court martial in Hasselt is already an old institution. It is a kind of local guard that provides security. Night watchmen go out every night and check for unwanted strangers, vagrants, and other scum that can make the city unsafe at night. They also watch out for open fires, arson and burglaries. All residents must join this vigilante force. To get relief from this work, one has to pay money, called drum money. Widows in particular pay this money just to avoid having to stand guard. Dulcken also buys off guard duty. This costs a guilder and a nickel every year.

The leadership of the civic guard is in the hands of a colonel; in addition, there are ensigns, sergeants and other leaders, honorary jobs that are mainly sought after by the rich in Hasselt.

Malicious slander I

In the spring of 1771, Dulcken faces a new problem. A member of the soldier garrison in Hasselt, cornet van Guldener is spreading malicious slander. All over Hasselt this pops up. The magistrate also hears about it and through mayor Heisman, advice is sought on 11 May from lawyer R. Sandberg in Zwolle. How to deal with this? Sandberg would like to have everything on paper so that he can issue an opinion. A day later, he receives the information from the magistrate. On 18 May, he advises informing the commander of the garrison of the matter, because the spreading of this slander causes a lot of commotion in Hasselt. But apparently little action is taken thereafter.

Dulcken is in Groningen at the time to sell harpsichords.

On September 22, the flame catches fire. In Jan Mansvelt's inn, a large number of people are seated and the conversation turns to Dulcken. Two persons, Hendrik Tracy de Wilde and officer Hendrik Stuijlen spread the slander Guldener started as being true. What was first told in back rooms is now proclaimed in public in the presence of many persons. A number of listeners are appalled.

The next day, Dulcken, who has just returned from Amsterdam, is told what has happened. The magistrate also hears about it and sends city secretary Exalto D'Almaras to Zwolle the same day to consult with lawyer Sandberg. The commander of the garrison is also informed. Because of the seriousness of the situation, the commander wants to inform the stadholder, since his subordinates are involved. Sandberg does not think this is a good idea. Meanwhile, the commander of the garrison has called Guldener in for questioning to find out on what grounds Guldener is spreading this slander. Guldener does not open up.

On 1 October, Dulcken learns that officer Stuijlen, involved in the conflict, is about to leave by ferry for Amsterdam to travel from there to the East Indies. He asks the magistrate to arrest Stuijlen immediately so that a trial can be brought against him. The magistrate does not respond and allows the officer to escape. Probably the magistrate is happy to get rid of Hendrik Stuijlen. A year earlier, the latter had also caused a disturbance, had been taken out of an inn drunk and the magistrate had even searched his house and confiscated documents. Then too, De Wilde and Guldener were involved. Stuijlen's departure did make it impossible for Dulcken to file a complaint against him.

Dulcken, through his lawyer Van Grevensteijn, filed charges on 8 October against de Wilde for malicious defamation. The demand is for de Wilde to publicly acknowledge that he acted wrongly by spreading lies, damaging Dulcken's good name and honour. It also demands 1,000 ducats as compensation. The complaint is accompanied by a report of a witness hearing. Four witnesses, café owner J. Mansvelt, J. Noest, commies G. Bax and J. Bode, confirm on 25 September what happened three days earlier.

Lawyer Sandberg gets hold of this report and writes his opinion on it in a note. The magistrate has to interrogate Guldener to try to find out what prompted this slander. This too yields nothing. On behalf of the magistrate, Exalto D'Almaras consults with the lawyer at various times.

De Wilde has engaged Hasselt-based lawyers Waterham and Zwolle-based R. Sandberg to defend him against Dulcken's charges. This means a double role for Sandberg. He advises the magistrate in the case and is also the accused's lawyer. This means the magistrate is no longer independent but has become a party in the case.

On 5 November, Dulcken has to appear at the town hall as De Wilde files a lawsuit against him. Sandberg comes up with the following story. In the spring of 1770, Dulcken comes to De Wilde because he has money problems. He wants to borrow money, but De Wilde has no money. De Wilde gives him two gold watches that Dulcken can pawn at the Bank van Lening in Zwolle in exchange for money. Dulcken returns from Zwolle with 112 guilders, keeps 100 himself and gives De Wilde 12 guilders. He promises to collect the watches from Zwolle again soon, but this does not happen. Finally, De Wilde has to buy back the watches himself with his own money. Now two years later, De Wilde demands his 100 guilders back, plus interest and other costs.

Captured

Meanwhile, other matters were at play. On 23 November 1771, Abraham Amthuijzen engaged lawyer R. Sandberg, who requested the seizure (pledge) of a number of harpsichords from Dulcken's workshop. It turns out that Dulcken has not yet repaid his debt from 1767. He is still 250 guilders in the red. On 27 November, the chattel prosecutor comes to Dulcken to say that he must appear at the town hall on 2 December to answer to him.

Dulcken immediately comes in deed. He asks Grevensteijn and Van Dingstee to apply for liens to prevent confiscation of his harpsichords. They send a letter to the magistrate asking what instruments are involved; those ready to be delivered to the buyer, harpsichords under construction or harpsichords under repair. They cannot just be sold because there are owners waiting for the instruments. On 2 December, Tede de Vries is nominated as guarantor. The pledge is provisionally accepted, and on 20 December Tede de Vries announces that he is officially guarantor for Dulcken.

Unfortunately for Dulcken, but Amthuijzen is not satisfied with that. On 3 January 1772, the rod carrier again comes to Dulcken's door and asks him to appear at the town hall on 7 January. He is given the message that money must be paid within a fortnight, or else confiscation will take place after six weeks.

De Wilde's lawyers are also not satisfied with Dulcken's attitude and still demand the pledging of some harpsichords.

Meanwhile, the atmosphere between Dulcken / Grevensteijn and the magistrate / Exalto D'Almaras is extremely tense. Dulcken expresses his anger at one of the mayors. This does not please the mayor. The magistrate then has Dulcken arrested and imprisoned. This probably happens immediately after 7 January. Grevensteijn later wrote to the States: ‘for he was so treated from time to time by the magistrates of Hasselt, that he was unable to earn a living for his wife and children, because they, without any lawful reason, grabbed him by the head, put him in a criminal prison, and made him stay there for several weeks, as if he were guilty of a major crime’. Grevensteijn sees no legal reason for this measure; on the contrary, it is pure rancour on the part of the magistrate or one of its members. Grevensteijn is probably referring to Exalto D'Almaras, the secretary who keeps popping up in the documents and also takes care of consultations with Sandberg. Dulcken was probably imprisoned in the council house, on the top floor in a small cell in the attic. The window in that cell looks out onto Nieuwstraat, where his house is fifty metres away.

On 11 January, Exalto D'Almaras travels to Zwolle to discuss Dulcken's detention with Sandberg. Sandberg probably advises him to release Dulcken because the magistrate is not in a strong legal position. How long he was imprisoned cannot be precisely determined. Grevensteijn speaks of several weeks of detention.

When the mayor releases him in mid-January 1772, he receives a bill with ‘the costs of detention of which he is not even allowed to enjoy a specification’, according to Grevensteijn, who spits his bile about this at the deputies in Zwolle.

Dulcken probably paid off his debt of 250 guilders in March 1772, either by giving money or one of his harpsichords being sold by the magistrate. But the litigation continues because subsequently Amthuijzen comes demanding that the loan for the peat, the batting cattle and the work of glazing also be paid. On 7 July, Grevensteijn writes a defence letter stating that the bill for the windows is new. No bill had ever been given to Dulcken before, nor any reminder. And no written evidence exists of the payments for peat and the cowherd. So pandering is unjust. And so the case drags on. The case about De Wilde's two watches also drags on.

During 1772 and 1773, the lawyers in both cases met almost weekly at the town hall. At issue is the lack of written evidence that has Dulcken's signature on it. When a signature does appear, Dulcken has to come to confirm that it is indeed his signature. It is about copies and lack of copies of court judgments. It's about claiming liens and giving liens. A legal battle that is totally bogged down. Added to this, Dulcken is often absent and his lawyers do not want to indicate his whereabouts. In July 1773, De Wilde is in money trouble and is placed under guardianship. His brother Frans de Wilde from Amsterdam (VOC secretary) acts as curator.

The prison in the attic of the town hall.

Agreement with court martial

In 6 April 1772, the deputies of the States of Overijssel indicate that Dulcken must come up with proof that the piece of land in the backyard belongs to him. Or he must declare under oath that he neither has nor has lost that proof. Grevensteijn countered that the court martial could also come up with evidence that the piece of land belongs to him. Cornet Guldener, a member of the court-martial, was appointed in 1755 by Messrs Van Hecht as a chargé d'affaires to arrange the sale of the premises. He sold the property to the court martial and is also responsible for the property that Dulcken later bought.

On 7 July, there is again contact between the court martial's lawyers and Dulcken's lawyers. Grevensteijn proposes to stop further proceedings through the States and the magistrate because of costs and to continue talking only as lawyers.

Each agrees and they come to an agreement to share the costs.

On 24 November Dulcken appears at the meeting of the court martial. ‘Requesting that the pending dispute between him on the one hand and the noble Manhaftige Krijgsraad on the other hand may be eliminated, presenting above the costs on his side to make up for the costs on the part of the court-martial a sum of one hundred and thirty-two guilders to be paid’. The fence may remain as the court martial put it up. On 18 December, Dulcken asks for a 14-day reprieve, but the court-martial disagrees and wants payment within 24 hours.

On New Year's Eve 1772, Dulcken brings his 132 guilders to the magistrate upon which the rod-bearer goes to Colonel Bode of the court martial with this money and wants to hand it to him. The latter does not want to deal with the money and the rood-bearer takes it back to Exalto D'Almeras, who keeps it in his possession for many years. For the court-martial is not over by then. In November 1773, lawyer Waterham submits another bill for 240, - which the court-martial has to pay. The court-martial seeks sureties for this and in January 1774 starts paying off this debt.

Malicious slander II

Meanwhile, the trial for malicious libel against De Wilde continues. Dulcken asks for a copy of Guldener's interrogation by the garrison commander, but does not get it. Again and again, notes are sent back and forth, with no progress. In December 1772, lawyer Sandberg comes up with a defence in which he states that Dulcken had better stop his action because it will not achieve anything anyway. He warns of high litigation costs. However, his narrative does finally include a report of Guldener's interrogation. But Guldener, a member of the garrison and court-martial, is kept out of the wind. The magistrate notes that only one person has been charged, namely De Wilde, and no other person can be inserted there.

On 8 June 1773, Sandberg presented his final defence. A long narrative with many Latin legal texts. He concludes that while De Wilde may have been morally wrong, he did nothing wrong legally. This is because when you say something is true unless the person you heard it from is a liar, that statement is itself true. So De Wilde cannot be prosecuted for what he said; the complaint is inadmissible. Sandberg concludes that Dulcken must pay the legal costs and may even be sued for calling De Wilde a liar.

Dulcken and his lawyer Grevensteijn appeal. In November 1773, they demand a copy of all documents relating to the case and that two independent lawyers be put on the case.

After that, there is silence, or documents are missing. Only in 1776 do documents talk about the case again, but about that later. All this time, Dulcken sits in uncertainty about what will happen to his complaint.

Gereformeerd / Hervormde Kerk te Hasselt

Church attestation

Dulcken and his wife attend the Reformed Church in the middle of town. They have their children baptised there and attend church there on Sundays. But they never became members due to circumstances and were therefore not allowed to partake of Holy Communion.

On 28 March 1771, before the whole De Wilde affair, Dulcken asked orally if he could become a member of the congregation. He brings with him his attestation, which he had thus not handed in ten years ago. The question is considered at the church council meeting, which considers the request.

On 27 September 1771, he sends a letter to the church council. He probably had a visit from church council members asking for more information. He explained that he wanted to move from Amsterdam to Kleve in 1756, at which time he received an attestation from the church council of Amsterdam. His plan did not go ahead due to unforeseen circumstances. The reason is probably that he then met his wife Catharina Koning and married her a year later. He built up a business in Amsterdam and when moving to Hasselt he neglected to hand in his attestation. In some conversations with pastor and elders, he indicated the same. Now he would like to become a member ‘as also D’ Heer Koning and others have become members’. Who he means by Mr King is not clear. Possibly a brother of his wife.

The church council discusses the letter, but even now cannot grant the request. It is felt that the attestation for Kleve issued 15 years ago is too old. Another reason is ‘a disgraceful rumour regarding his reverend brought in by the magistrate and substantiated by witnesses’. This probably refers to the malicious slander spread that week by De Wilde. One of the church council members is also one of the four mayors and knows first-hand what is going on. They want more information from the magistrate before making a decision. Dulcken then asks for his old attestation back.On 20 December 1771, the minutes of the church council record that Dulcken's application for membership will not be considered unless Dulcken comes up with a new application. And there is none yet. The minutes of 17 April 1772 contain the same phrase. Dulcken's request is not yet in, so the church council does nothing

Not until 2 October 1772 is there a new request from Dulcken: ‘a humble begging’, as he himself calls it. In it, he writes that he realises his attestation was too old. He therefore makes the request again, but unfortunately he does not know why the church council did not grant his previous request. He promises to submit to the church council if a settlement can be reached.

The church council agrees. They decide that Dulcken may come to the next church council meeting to answer some questions. The condition is that no bad news comes in about him in the meantime. The church council members are asked to take heed of Dulcken's comings and goings in the near future.

At the next church council meeting on 11 November 1772, there is uncertainty about the way forward. The only item on the agenda is: how to deal with Dulcken's request. It is decided to record the decision of 2 October 1772 in a resolution.

On 21 December 1772, there is another church council meeting. Dulcken is invited by the sexton to attend part of it. But before Dulcken is called in, a major disagreement arises in the church council. Five members want the handling of the Dulcken case to be based on the church council decision of 27 September 1771 i.e. the church council must first find out from the magistrate what kind of person Dulcken is.

Four members (plus one absent member) wish to proceed on the basis of the decision of 2 October 1772 i.e. Dulcken is invited for interview and if no strange things have happened in between, he is accepted as a member. Conclusion: nothing has been brought forward to show that strange things have happened. So we can invite him. The pastor and the presiding officer ask for a copy of the decree (1771) that a communication from the magistrate should be awaited first. The matter is deadlocked. Finally, Dulcken is let in and is told that the decision of 27 September 1771 stands. The magistrate must clarify first. He protests against it and says his protest should be written down. The presiding officer asks if he wishes to put forward anything further. The short answer is ‘no’.

He leaves the meeting, but he reflects, asks through the sexton if he may re-enter. He asks for a copy of the resolution. The sexton takes him out of the meeting room again. ‘I shall have se Heeren,’ the church council members hear him shout several more times, whereupon they decide that he is indeed entitled to it, and instruct the sexton to provide him with a copy. That is his last conversation with the church council. The membership list shows that Dulcken never became a member of the congregation. A two-year battle fought for nothing, thanks to the magistrate's influence on the church council.

The skipper issue

Among the pile of letters received by the magistrate in 1772 is also a curious letter from Zwolle dated 16 June 1772. The letter was written by the deputies of the States of Overijssel against the following background. Hasselt is a poverty-stricken town and the magistrate is making frantic efforts to bring in money. In 1771, the magistrate decided that all fishing boats sailing from the Zuiderzee and Schokland, to Zwolle to sell their catch at the fish market, must first dock in Hasselt. They must unload their cargo on the quay at the fish market and pay market money for it. A nice source of income for the town.

View of Hasselt from the other side of the Zwarte Water.

The documents describe how four men from the city guard overpower a ship and force the skipper to dock. Other ships are also stopped and forced to dock. The skippers, as well as the city of Zwolle, are outraged. Hasselt invokes centuries-old rights and refuses to stop.

The letter of 16 June gives a picture of how Dulcken gets involved in this conflict. He held a signature campaign just before 25 January, the Pauli choice, among boaters and other citizens of Hasselt. On this day, the new members of the magistrate are elected. So Dulcken must have started his signature campaign right after he was released from prison.

Does Dulcken feel connected to the fate of the boatmen because he often uses their services to transport harpsichords elsewhere? In any case, he knows many of them. The boatmen write a letter of protest to the stadholder Prince William the Fifth, and Dulcken, or one of his friends, goes around collecting signatures.

Dulcken takes these to hand them over to the prince. This is a dangerous undertaking, as the magistrate may see it as a hostile action. The prince takes note of the letter and responds to it. This response also states that the signatures under the letter were lost because that part was burnt.

The letter of 16 June 1772 holds Dulcken responsible for this. Did Dulcken feel unsafe en route to the prince in Amsterdam? The magistrate would be only too happy to know who the signatories are. The advice to the magistrate is to arrest Dulcken and force him to tell the truth.

Dulcken just has to state, ‘where, when, and in whose presence and why that burning has taken place’. And he must confirm with an oath that he is telling the truth. On the basis of what Dulcken has to declare, the deputies will then advise what to do next with him.

No other documents on this incident can be found; it is not known how it ended. The conflict over the boatmen leads to major disagreements between Zwolle and Hasselt, also involving the States of Overijssel. A year of bickering does take place, with the magistrate of Hasselt finally losing out.

In August 1772, the ninth child in the Dulcken family was born. Catharina was baptised in the Reformed Church on 19 August.

Back to Antwerp 1773 -1776

The pianoforte

Until now, Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken has mainly been involved in manufacturing harpsichords, repairing them and repairing organs. But the market for harpsichords became saturated in the 1970s and 1980s. Instruments very similar to the harpsichord but played in a different way appear on the market in various places in Europe. This is a new invention and the instruments are called pianoforte. With a harpsichord, the sound is created when a plectrum is stroked along a string, while with the pianoforte a hammer strikes the string. While the harpsichord sounds loud and soft only through registration changes, with the pianoforte it is easier, as one can strike the key hard and soft. Literally translated, pianoforte means soft-hard. This requires completely different mechanics.

Dulcken also turns to building pianoforte from 1774. Instead of hundreds of docks, Dulcken now has to make hammers. He covers the head of the hammer with leather. The kind of leather and how tightly it is stretched determine the mood of the sound. Dulcken probably also started experimenting with pianoforte instruments in Hasselt. For this, he uses the sound box and strings of the harpsichord. But he uses a new mechanism. All over Europe, people are experimenting to make instruments with the most beautiful sounds. Each one does so in its own way.

The first to build a kind of pianoforte is Bartelomeo Cristofori in Italy around 1700. Other countries claim credit for their own inhabitants: Germany has long claimed the invention of the pianoforte for Christoph Gottlieb Schröter, France for Jean Marius and England for Father Wood. Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken, for instance, was the first to market his pianoforte in the Netherlands.

Antwerpen

Dulcken moves to Antwerp in 1773, the city where his father built so many world-famous harpsichords. His home address remains Hasselt, where his wife and children continue to live, but his work address is Antwerp. He probably has two reasons for this. Firstly, he is not sure of his life in Hasselt. He may now have solved the problem with the court martial and with Van Amthuijzen as best he can, but the magistrate's actions are so unpredictable that he could just be arrested again. Grevensteijn therefore blames the magistrate for the fact that Dulcken was bullied away, leaving him separated from his wife and children for a long time. The second reason is that he sees better opportunities in Antwerp to market his new invention.

His departure for Antwerp has major consequences for the three servants who build his harpsichords in Hasselt. The deeds mention three servants by name: Johan Gerlach Lauch, J.L. Reusch, both originally from Germany, and Jacob Snel. Not only are they suddenly unemployed, but Dulcken failed to pay them wages for 1772 and 1773. Johan Gerlach still demands 443 guilders, J.L. Reusch 77 guilders and 3 pennies and Jacob 92 guilders. On 16 April 1773, they ask for pledges on the unfinished harpsichords. A week later they return to this. They now demand pawn on the house on Nieuwstraat and on the workshop on Hofstraat, because they realise the harpsichords will not fetch enough. Dulcken probably paid the overdue wages immediately, because the pledge is not enforced. Meanwhile, he has rented the residential part of the workshop on Hofstraat to the widow Wilhelmina van Reen. Her mother lives next door and is married to Klaas Admiraal, the painter.

Dulcken takes up residence in the logement de Arent on the Vrijdagsmarkt. In the Gazette of Antwerp of 10 September 1773, there is an advertisement praising his work. ‘Jean Louis Dulcken, (eldest son of the deceased Daniël Dulcken), master organ and harpsichord maker present at Antwerp, with the intention of living there in due course, presenting his service to make or repair organs or harpsichords. He is staying in the Arent near the Vrijdagsmerkt, where 8 days later a new piece of his work will be exhibited, being a harpsichord with double keyboards’.

And in the Gazette of Ghent on 6 July 1775:

Sieur Louis DULCKEN of Antwerp, oldest son of Daniel, advertises, in order to make his knowledge known, that he has had two Clavecin-Bellen brought here, namely a Steirt-Stuk and a Forte piano of his work, being a new invention, because one can diminue and casse the tone of the two without any commodity, which pieces are for sale and can be seen for a few days in the Herberge den Duydsch by S. Jacobs Kerke within this city. Jacobs Kerke within this City, where enthusiasts may find them, to examine them. Note. Deze Uytvindinge van diminuëeren en casseeren kan aen alle Stukken gebragt worden’.

Also in this ad, Dulcken profiles himself as the son of the famous Daniel. He now also offers a fortepiano made by himself. One can ‘diminish and casse’ on this pianoforte, i.e. make the strength of the tone softer and softer, as well as louder.

In Antwerp, he applies to the city council to be granted the same rights as his father had, namely to be able to export his harpsichords without problems and costs. The city council does not agree. It thinks he has been away from Antwerp for too long, AND he is not a member of the St Lucas guild. The guild for artists is not open to craftsmen. So he does not have the same rights as an artist.

The church attestation

Dulcken tries to connect with his parents' church. They were members of the small Reformed Church: the Olijfberg where Johannes Diepelius was pastor. Dulcken was 20 years old when he left Antwerp and experienced the pastor closely in his youth. His father was an elder and the pastor must have often visited their home. Sunday meetings were also regularly at congregation members' homes.

A letter dated 26 October 1774 has been preserved from Rev Diepelius to the magistrate of Hasselt. It is clear from that letter that Dulcken could not be admitted without question. In his letter, the pastor hints at an incident that took place 20 years ago; the reason for Dulcken's departure from Antwerp. Dulcken can also only hand over an attestation from Amsterdam that is almost 20 years old.

The vicar has been told stories by a servant of Dulcken about what happened in Hasselt. Dulcken reacts furiously. In Hasselt he was rejected and now the pastor rejects him on the basis of gossip. Rev Diepelius consults the fellow ministers present at the Breda synod. He is advised to ask the city council in Amsterdam and Hasselt for an attestation for Dulcken. In Amsterdam, the pastor knows mayor Daniel de Dieu. This one can tell little about Dulcken except that there had been something with the poorhouse. Reason why Dulcken was no longer allowed to come to his home. So the vicar now turns to the magistrate of Hasselt to ask: ‘are all the gossip he has heard about Dulcken true’? To ‘ask this, is by no means hate, orte wederwraak’, showing that he gives Dulcken little chance.

We would like to read the magistrate's reply, but unfortunately it has not been found. What is clear is that Dulcken and his family never became members of the Reformed Church on the Mount of Olives.

Dulcken probably set up a workshop in Antwerp where he devoted himself to making the pianoforte. He sells these instruments in Antwerp, Ghent and also in Leuven. Meanwhile, he regularly returns to Hasselt where his family lives.

Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken jr.

1761 - 1768

Johannes Lodewijk Dulcken was born into the family of Johan Lodewijk Dulcken and Catharina Koning in the summer of 1761 and baptised on 9 August 1761 in the Gereformeerde Kerk in Amsterdam/ Sloterdijk. His call sign is Louis. He has a brother, Daniel Lodewijk, who is one year old and a big sister, Susan Maria, who is four. His father is a master organ and harpsichord builder and they live next to the Carthusian cemetery in Amsterdam.

As a small baby, less than six months old, he moves to Hasselt in early 1762. There, his father rented a large house in Nieuwstraat.

Nothing of his life in Hasselt can be found in the archives, but a picture can be drawn of his living environment and the events that took place there in his young life. He may later remember the following from his childhood in Hasselt:

When he is almost two, a little brother is born. His parents name him Johan Daniël, after his famous grandfather. Unfortunately, this little brother does not live to be one year old. On 20 April 1764, he is buried in the cemetery behind the Reformed Church. Still in the same year, another little brother is born on 22 July, again named Johan Daniël.

1765

Johannes Lodewijk is now old enough to explore the world outside the house.

His parents' house is on Nieuwstraat; this street runs from Markt, where the town hall is, to the canal. Across the canal is a bridge with a lock in the canal that also serves as a flood barrier. Across the canal, on Gasthuissteeg, stands an old monastery building; the alley ends in a rampart with city walls.

C. Springer, het oude Gasthuis aan de Gasthuissteeg.(1862)

Along Nieuwstraat, paved with cobblestones, are houses and the workshop of a blacksmith. To the right of his house is Regenboogsteeg, formerly also called Ragebolsteeg. In Regenboogsteeg is a tobacco plantation that belonged to the Van Benthem family, and also a roof tile factory. Both are no longer used, but you can still see where they stood. Behind their house is a large garden, where his father grows vegetables. Between the garden and Rainbow Street is a wall, with a passage to the street at the end.

In the spring of 1766, Johannes Ferdinandus is born and baptised on 16 March. The little boy dies before he is six months old. Once again there is grief in the family.

Meanwhile, Johannes Lodewijk turns six, the age when he can go to school. This means he is taught reading, spelling, numeracy and writing. To learn these basic skills, his parents have to pay 18 guilders a year. He can attend school every morning and afternoon and is free on Wednesday afternoons.

In January 1768, another little brother is born, baptised on 13 January. His parents name him Ferdinandus. The little boy lives only a month and again there is grief. Unfortunately, it is common for children to die at a young age. A large proportion of children do not make it to the age of 20. Children die of childhood diseases, poor drinking water and because parents are in poverty.

Walking through the streets of Hasselt, Louis sees poverty everywhere. The houses are poorly maintained; sometimes they are hovels. In some places where houses have been demolished, empty spaces appear in the streets. There are also many farms in the city, often with a dung heap on the side of the street. The gutter, which provides drainage for rainwater, is sometimes open, but often there is a plank over it, making the street less dirty.

He sees collection boxes hanging in various places. Wealthier residents can put their contributions there, which can be used to help poor people by the diaconate. In December 1768, Johannes was born. His call sign is Jan. He is baptised in the big church on Boxing Day. They are now five children at home; his eldest sister Susan Maria is just 11.

When they go to church, he and his little brother and sister sit with mother. Father sits in another part of the church with the men. Close to the main door is a pulpit. Usually Pastor Noortbergh preaches.

Interieur Hervormde Kerk Hasselt.

There is no organ in the church; it was destroyed by lightning and fire 50 years ago. The church and the city council have no money to have a new organ made. His father could well do it; he has built organs before. Now the place is empty and when there is singing, there is a cantor who indicates the melody. Hermen Huninck is an organist, but probably has little to do since the fire of 1725.

His father is often away from home; then he leaves on a barge to Amsterdam, sometimes even to Middelburg.

He then takes one or two harpsichords with him. They lug these from their house through Nieuwstraat, across Markt and then via Veersteeg to Veerpoort. Outside the Veerpoort lies the Zwartewater. From there, the barges go to various places along the Zuiderzee. Each turn boatman has his own destination. His father often goes with him; so he knows all the skippers.

When father is away, the servant just keeps working on the harpsichords that are in the workshop. The servant also lives in their home and has his bedroom at the very top of the house.

Sometimes a man comes to the door with a note, Mr Van der Werff. He is robed and brings a message from the mayor or the council. His father then has to appear at the town hall again. Sometimes father is not at home and then mother or his eldest sister takes the paper. When this man comes to the door, Louis already knows exactly what he has come to do. Sometimes there is more to it, as when the rod-bearer and some helpers bring two harpsichords.

1769

When Johannes Lodewijk was eight years old (1769), his father bought the house where they had been living for six years, and on Hofstraat he bought a workshop

This is necessary because the house on Nieuwstraat is becoming too small. Because Grandma Dulcken has come to live with them, there is a lack of space. When grandma, who lived in Brussels, comes to live with them, she is ± 65. Grandpa, whom he never knew, died long ago.

His father brings all kinds of materials to Hofstraat and sets up his workshop there (Plot A262) When Louis walks to the workshop, he sees small businesses and shabby houses in Hofstraat. At the end of the street is a number of cottages next to each other, which people call the ‘Armenstraat’. Often, because of the smell, there are arguments over the gutter that runs down Hofstraat.

Werkplaats Dulcken links

Next to the residence on Nieuwstraat is a large building, owned by the court martial. Louis often sees people going in and out there. In the evening, the night guards come there, going through the town two by two, and sometimes he hears them shouting. Occasionally there is also a whole group at once; then the men march through the town in a column. The night guards carry weapons. At night, music can often be heard coming from the house of the court martial. Then there is a meeting or party when the guilds meet there. People then call the house Guild House.

His father has a quarrel with the lords of the court martial. The big garden they had got a lot smaller. His father then bought a piece of land behind the Wall, where he created a garden. De groente wordt in de herfst in de kelder opgeborgen. Every year father buys a cow or a pig in the autumn, which he has slaughtered by the Jewish butcher Salomon Abrahams or Albert Berend van der Werff . At home, the meat is smoked so they have food all winter.

1772

By now Louis has turned 11 and is big enough to walk around the city by himself. Walking out of Nieuwstraat, he comes to the canal where mostly rich people live.

C. Springer, Scenery on the Hasselt canal.

Oil lanterns are everywhere in town, especially in the wealthier neighbourhoods such as Hoogstraat and Ridderstraat; some 30 of them. A little further on he comes to the Venepoort, which gives access to the dyke to Zwartsluis and the post road to Staphorst. Turning left, he goes along the city wall to the Raampoort, passing through the poor neighbourhood. Further on, he comes to the Veerpoort, which separates the town from the quay with ships. Along the Vispoort, he walks to the Enkpoort, which gives access to the dike to Zwolle. This is an old stone dike; in a bit of a storm, the water sloshes against it. Another short stretch along the canal and then he is home again; a walk of about 1,200 metres.